A case for posthumanism: Part 3 - Taking sides

”If you desired to change the world, where would you start? With yourself or others?” - Alexander Solzhenitsyn

Introduction

In this third part of this series on posthumanism (Part 1 and Part 2), I had intended to define some key principles for thinking with posthumanism. But as I worked on that piece, I found I needed to be clearer about my own philosophical orientation, so that I didn’t give the impression that my list of key principles could be seen as definitive. Posthumanism is a wide discipline covering diverse philosophical orientations, and some of these are about as far apart ontologically as you can get.

Graham Harman’s Object Oriented Ontology is dismissive of Karen Barad’s agential realism (as we will see below). Ray Brassier’s nihilism is the polar opposite of Arjen Kleinherenbrink’s life-affirming Deleuzian machine ontology. Manuel DeLanda’s assemblage theory is realist while David Lapoujade’s aberrant movement is not. Rosi Braidotti’s nomadic subjectivity has nothing to say about Tristan Garcia’s form and object. And while Tim Morton’s hyperobjects bear some similarities to Donna Haraway’s cyborg hybridity and Luce Irigaray’s vegetal being, Erin Manning’s relationscapes, Jane Bennett’s thing-power, Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory, and Thomas Lemke’s governmentality of things, all strike out in notably different directions.

Given this dizzying array of posthuman philosophies, it is perhaps understandable that authors try to narrow things down a bit, as Rebekah Sheldon has done by suggesting that;

‘Within this broad and interdisciplinary movement, two methods have attained particular visibility: speculative realism, especially object-oriented ontology, and new materialism, especially feminist new materialism’ (Sheldon, 2015, p. 193).

I think there’s some merit in offering this binary, not because it defines a difference between approaches based on gendered identity politics, but because it highlights some important ontological and epistemological differences that anyone coming into posthumanism would be wise to wrestle with. So let’s take a moment to unpack the two sides Sheldon highlights.

Speculative Realism and New Materialism

In the footnotes to Part 2 of this series, I commented that “If I were a poststructural feminist, I might be tempted to point out that the vast majority of critical posthumanists are women, whereas those in a radical ‘anti-humanism’ are almost exclusively men” (link). Well, Rebekah Sheldon makes the same point in her excellent overview of the problems critical feminists have with speculative realism (Sheldon, 2015).

Writers like Graham Harman, Levi Bryant, Nick Srniceck, and Quentin Meillassoux, she argues, will tell the history of the posthuman turn without even mentioning women like Stacy Alaimo, Karen Barad, Jane Bennett, Rosi Braidotti, Judith Butler, Melinda Cooper, Elizabeth Grosz, Donna Haraway, Valerie Hartouni, N. Katherine Hayles, Myra J. Hird, Luce Irigaray, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Annemarie Mol, or Celia Roberts.

’The absence of women from this story of succession is remarkable both for its casual and apparently unwitting embrace of patrilineation, but also, and more incisively, for the distortions it relies on to produce such a clean line of descent’ (Sheldon, 2015, p. 203, see also a similar comment by Lemke, 2021, p.38).

In effect, speculative realism (SR) and Object Oriented Ontology (OOO) have relegated critical posthumanism to a footnote ‘within its own autobiography’ (Sheldon, 2015, p.204).

But this ignorance, Sheldon argues, only masks a deeper ontological dismissal of the critical problems that motivated the critical posthuman turn in the first place. Simply put, SR and OOO say nothing about ongoing oppression and, in their dismissal, enable or even perpetuate it.

Feminist new materialism (FNM), which has become the fulcrum around which a great deal of critical posthumanism turns, broadly argues for:

A critique of scientific neutrality;

The role of culture in mediating between things and our experience of them;

The non-discursive agency of other-than-human forces (Hird & Roberts, 2011);

Human critical humility, and an accompanying respect for the ‘vivacity, vulnerability, and sometimes… surly intransigence of nature’ (Sheldon, 2015, p. 195).

But perhaps the defining feature of FNM is its focus on the direct material consequences of human knowledge systems. Epistemology for feminist new materialists is ‘emphatically relational’ (Sheldon, 2015, p. 195), hence why, Sheldon argues, feminist theorists use so many phrases with double articulations; phrases like nature–culture, material–discursive, and intra–action. Reality is constituted by the interplay of ideas and things. Entities are defined both by their ability to affect and be affected by others: what Fox and Alldred called an ‘affect economy’ (Fox & Alldred, 2016).

OOO, by contrast, sees entities as having a mind-independent reality, but also a reality that is fundamentally inaccessible. No entity can ever be fully exhausted by its relations. Following Heidegger and Husserl, Graham Harman — one of the chief proponents of OOO — argues that all entities share the same fourfold structure with surface effects that objects encounter when they interact, concealing an ontologically withdrawn ‘core’.

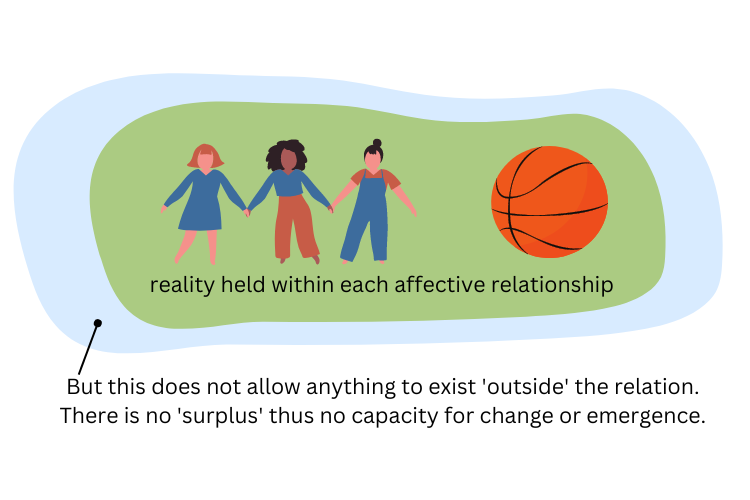

OOO argues that the concept of an affect economy fails on two counts: firstly because it cannot explain change; because if everything that exists is encompassed by the relation between entities, there can be no surplus: no potential for anything new to emerge beyond the boundary of the two entities in relation. If theories of affect (a key feature of FNM) did allow for a zone of indeterminacy outside of the affective relation, then reality cannot be explained by affect alone, as its proponents suggest. So, in the eyes of speculative realists, affect fails because it cannot explain change or emergence.

But affect also fails because it cannot account for a mind-independent reality. Kantian philosophy encouraged us to believe that the world only came into existence with the arrival of a mind that was sophisticated enough to conceive it. FNM argues exactly this: that our knowledge of the world is fundamentally a learned act; that ‘experience and ideation emerge out of structures of knowledge’ (Sheldon, 2015, p. 200). More than this, though, FNM argues that these structures are defined by historical discourses of sex and gender (ibid).

There is a turbulent political dispute here then, with FNM advocates arguing that SR and OOO theorists are engaged in ‘the seemingly never-ending process of pushing back against new, creative ways to suppress emancipatory project(s)’ (ibid), while realists like Manuel DeLanda ungraciously argues that “I have even more contempt for those who appeal to the worst parts of science - such as [Karen] Barad” (DeLanda & Harman, 2017, p. 7).

Sheldon is perhaps right then to suggest that the relationship between SR and FNM is ‘particularly rancorous’ (Sheldon, 2015, p. 194);

’The antagonism between these two fields is in some ways easily understood. After all, feminism is historically constituted around human subjectivity, sexed specificity, and the sculpting effects of culture. Add to that the origin of feminists’ engagement with the sciences in a critique of scientific neutrality—a critique that argues quite precisely for the intercalation of culture between things and our experiences of them—and it becomes clear why the two fields have been wary of each other’ (Sheldon, 2015, p. 195).

In Sheldon’s view, the dispute between these two main branches of posthumanism recapitulates;

‘the hoariest of philosophical binaries: the form/matter distinction’ (ibid), in which OOO privileges form as an aloof, detached, non-agential entity – akin to the classical notion of one’s sex, where FNM is concerned with matter and the dynamic, mobile, and fluid notion of nonhuman agency - akin to the contemporary reading of gender’ (ibid).

And given what is at stake, it is perhaps understandable that a new wave of poststructural feminists are eager to hold on to the emancipatory drive of the past whilst, at the same time, opening new critical lines of flight.

Susan Bordo recently made the stakes clear;

’Since the election of Trump, preceded by a misogynist campaign that was shocking in its hostility and followed by the stripping away of rights we’d counted on for 50 years, it’s become clearer and clearer that we are far from “post” feminism’ (Bordo, 2023).

On the surface, it would seem that a crucial point of difference between FNM and SR lies in the way they relate to the human. In FNM relations precede ‘being’, but it is this being-in-relation that then brings about new relations. Barad calls these intra-actions, with matter and discourse co-constituting one another. Besides Karen Barad’s Meeting the Universe Half Way (Barad et al., 1996), there are also some excellent examples of this in Annemarie Mol’s The body multiple (Mol, 2002), Myra Hird’s The origins of sociable life (Hird, 2009), and Stacy Almao’s Bodily natures (Alaimo, 2010).

There is little doubt, though, that FNM explicitly retains a place for the human because, ultimately, it wants to offer new modes of critique for the kinds of oppression and marginalisation that feminism has fought against for aeons. In this sense, then, it struggles sometimes to identify in what ways it is post-human.

OOO by contrast, appears to be entirely nonhuman, making no apparent effort to single out the human from any other entity in its radically flat ontology. SR and OOO recognise matter only as a ‘fixed, flat, or law-like substrate’ (Bennett, 2015, p. 233). Harman even goes as far as to say that “Any philosophy that is intrinsically committed to human subjects and dead matter as two sides of a great ontological divide…. Fails the flat ontology test” (DeLanda & Harman, 2017, pp. 85-86). Humans are merely one entity among a universe of others.

And yet, the sheer strangeness of objects that SR celebrates, resurrects a ‘blunt form of subjectivism that not only remains within the humanist frame but is also distinctly gendered’ (Taylor, 2016, p. 210). Who is it, Carol Taylor asks, that renders the ‘alien’ object knowable? By whose criteria is this rendering deemed to be ’satisfactory’ (ibid)? Tellingly;

’the human who is reinstalled as recorder of traces is indubitably male, embodying an opaque set of values, and judging from a distance’ (ibid).

From a critical posthuman standpoint, SR and OOO make no attempt to link the differential power of humans to nonhuman objects;

’at the very moment when humans have caused a state shift in the earth’s biosphere and are presiding over a mass extinction, we are witness to the ascendency of a social theory that massively redistributes agency to the nonhuman and promotes withdrawal as the primary mode of being’ (Campbell et al., 2019, pp. 129-130).

The politics of posthumanism

Clearly then, the battle for the soul of posthumanism is a deeply political one, especially when it comes to critical posthumanism.

But herein, for me, lies one of its weaknesses, because it is sometimes hard to see what it offers to critical questions of anthropocentrism, patriarchy, rampant capitalism, human exploitation, and alienation that is not already there in the critical theory literature. Critical posthumanism bears some striking similarities to intersectional theory, but perhaps with greater attention paid to the mattering of things. It remains, however, a project fundamentally underpinned by an orientation to human social life.

And there is nothing wrong with this. The more tools we can have that bring about critical change the better. But these tools have so far proven to be only partially successful, as Susan Bordo suggests above.

For me, the real promise of posthumanism lies in its ability to break the gravitational pull of the earth and break the long history of human-centred thinking that has beset thinkers in the West for centuries. In doing so, I believe posthumanism offers the promise of some really radical ideas for future life for all.

Perhaps the most emotionally challenging advocate of this radical approach to posthumanism is Ray Brassier, whose nihilism argues that the logical conclusion of the hubristic human search for objective reality will the ultimate destruction of the manifest image of man (Brassier, 2007). But rather than seeing this absolute nihilism as a depressingly hopeless image of the future, Brassier argues that if we can get past the idea of our own extinction, we might be better placed to understand the full extent of thought as it exists already, beyond the boundaries of our anthropocentrism.

In many ways, it’s a powerful way to help us break our tendency to think like humans, but it fails on two counts: firstly, because it bears many resemblances to ancient stoic and skeptical philosophy in which it is wisdom, not destruction, that results from our rejection of our humanism; and secondly, because rather than engendering a cosmic nihilism, an ultimate form of subjective idealism might be the result of stripping away our human qualities, because all the Ego would be left with would be knowing ‘nothing but itself and its own ideas’ (Woodward, 2015, p. 33).

And this, for me at least, is where Deleuze’s philosophy of life comes into its own, because Deleuze sees ‘life’ as a motive force within all things: as an animating, dynamic, creative energy that is the expression of ‘ineliminable difference on the basis of an absolute univocity of being’ (Roffe, 2015, p. 43). In other words: every entity is unique in its difference; encounters with other entities are the engine of creativity; every encounter creates a new ‘third’ entity that shares the same univocal structure as its progenitors, but is unique in its qualitative difference; and that this repetition of difference means that the cosmos is in a constant process of becoming, never stabilised sufficiently to constitute static ’being’.

What will follow in the next post will be a set of key principles that might, just might, allow us to break the gravitational pull of the earth and allow us to develop radically new ways to think about health and healthcare, not as person-centred disciplines, but as philosophies for all kinds of new becomings.

Apologies again for the lengthy diversion, but it felt necessary to set this debate down before pushing on.

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts, comments, challenges, and questions. So please add comments below and pass this post on to anyone you think might be interested.

References

Alaimo, S. (2010). Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self. Indiana University Press.

Barad, K., Nelson, L. H., & Nelson, J. (1996). Meeting the universe half way: Realism and social constructivism without contradiction. In L. H. Nelson & J. Nelson (Eds.), Feminism, science and the philosophy of science (pp. 161-194). Kluwer.

Bennett, J. (2015). Systems and things: On vital materialism and object-oriented philoosphy. In R. Grusin (Ed.), The Nonhuman Turn (pp. 223-239).

Bordo, S. (2023). Goodbye, postfeminism. https://susanbordo.substack.com/p/goodbye-postfeminism

Brassier, R. (2007). Nihil Unbound: Enlightenment and Extinction. Palgrave MacMillan.

Campbell, N., Dunne, S., & Dylan-Ennis, P. (2019). Graham Harman, immaterialism: Objects and social theory. Theory, Culture & Society, 36(3), 121-137. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0263276418824638

DeLanda, M., & Harman, G. (2017). The Rise of Realism. John Wiley & Sons.

Fox, N. J., & Alldred, P. (2016). Sociology and the New Materialism: Theory, Research, Action. Sage.

Hird, M. (2009). The Origins of Sociable Life: Evolution After Science Studies. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hird, M. J., & Roberts, C. (2011). Feminism theorises the nonhuman. Feminist Theory, 12(2), 109-117. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1464700111404365

Mol, A. (2002). The body multiple: Ontology in medical practice. Duke University Press.

Roffe, J. (2015). Objectal Human: On the Place of Psychic Systems in Difference and Repetition. In H. Stark & J. Roffe (Eds.), Deleuze and the Non/Human (pp. 42-59). Palgrave Macmillan.

Sheldon, R. (2015). Form/matter/chora: Object-oriented ontology and feminist new materialism. In R. Grusin (Ed.), The Nonhuman Turn (pp. 193-222).

Taylor, C. A. (2016). Close encounters of a critical kind: A diffractive musing in/between new material feminism and object-oriented ontology. Cultural Studies? Critical Methodologies, 16(2), 201-212. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1532708616636145

Woodward, A. (2015). Nonhuman life. In H. Stark & J. Roffe (Eds.), Deleuze and the Non/Human (pp. 25-41). Palgrave Macmillan.

In "Assemblage Theory & Method", Ian Buchanan says that one of the main functions of Deleuze's (posthuman) philosophy is to overturn Platonism, particularly on the question of desire (not as lack, but as creative force). Whether this is just another footnote to Plato will depend, I suppose, on whether Deleuze remains as long in people's mind as Plato.

Interesting review. I wonder if “posthumanism”, like any other post, is fundamentally a gesture trapped in its own historical self-referential construct. Looking forward to the days of pre-post (or post-pre, if you prefer).