Touching through

Hello everyone. I hope you all had some kind of break over the holidays and are looking forward to 2025.

I'm fully back at work now after a lovely summer holiday and itching to get back to it. I've got lots of writing to do this year, including breaking the back of a new book on the philosophy of physical therapies.

This book has been renting a room in my life for about 15 years so far but I’ve only been working on it seriously for the last five years. This year feels like the year where it starts to take shape.

Part of the slow grind of the work has been that it’s involved a lot of digging. And when you dig into the physical therapies it's amazing what you find.

For example, a couple of weeks ago I was listening to a podcast interview with two lawyers who were debating the question of what it meant to touch through something. Initially this didn't sound like a particularly interesting subject, but then the two lawyers started unpacking its significance and I started to realise just how relevant it was to the work I was doing.

In the first instance, deciding on when someone has touched through something is vital in all cases of assault. As Robbie Morgan and Will Hornett put it, if “assault is defined as unwanted touching, we need to know whether touching has taken place before we can decide whether an assault has taken place”.

Simply enough you might think?

But not so. In reality there are many conditions that need to be met for something to actually be said to be touching.

For instance, if you're wearing clothes and you claim that I've touched you inappropriately, could I make my defence on the basis that I didn't touch you, per se, but rather the coat you were wearing? I didn't touch “you” at all.

This argument relies on the presence of some interposing material, but some materials are thicker than others. Most people would probably accept that you can't touch somebody through a brick wall, but what about a very thin fabric or even a thin layer of sunblock? At what point is the interposing material thin enough to be insignificant? And who decides?

A lot of the questions around what actually constitutes touch in the legal sense arose with the perjury case against Bill Clinton when he was accused of having sexual contact with Monica Lewinsky.

Clinton’s lawyers asked the prosecution to provide an exact definition of what sexual contact meant so that they might give their interpretation of Clinton’s actions based on how these conditions had or hadn’t been met.

Evidence of simple tactile ‘contact’ proved not to be enough because of the problem of interposing material. In essence, if I'm touching one thing and that thing is touching another thing and that's touching you, then, in theory, everyone is touching everyone.

But equally you can't touch someone through air, because this would also mean everyone is touching everything all of the time.

Added to this, applying a principle of causation is also a problem because to what extent does my touch cause something else to happen? Do I need to see a a red mark or a slight depression on your skin to verify that I have touched you?

And what about indirect contact? If I jump on one side of a trampoline and launch you into the air on the other side, has my contact constituted causal touch? If so, how far from the original action does this affect extend –1 m, 10 km, 1,000 km?

What if you and I are playing tug-of-war? I might be able to pull you over or let go and make your tumble, but am I touching you through the rope?

Morgan and Hornett go on to discuss lots of other challenges to the simple idea of what it means to touch through something, but there are two aspects of this that really struck me as interesting.

The first is the relevance of this for all the kinds of touch that are claimed by physiotherapists and others as a special skills worth protecting.

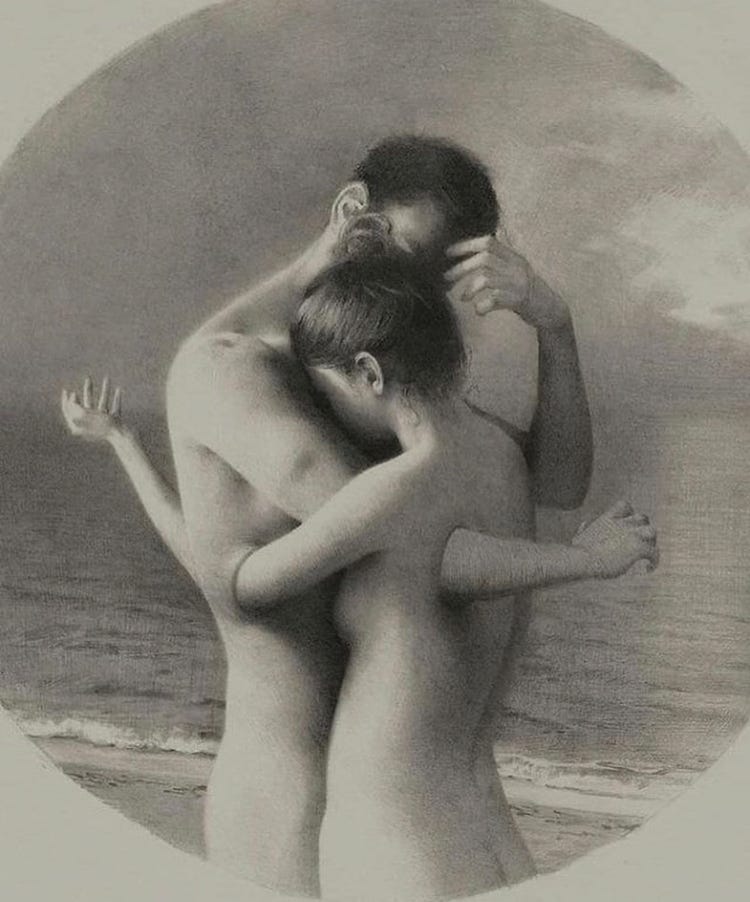

This kind of therapeutic work depends on a clear understanding of what it means to touch another person. What is it exactly that we are touching? Is it the skin, the sensory nerve endings, the brain indirectly through the neural network, or the subjective phenomenon that is “the person”?

The second is a process philosophy problem based in parts on my belief that everything is actually touching everything else all of the time.

To quote Arjen Kleinherenbrink, everything has a shot and affecting everything else in the cosmos, even if some things are specially distant (Kleinherenbrink, 2018). In fact, modern physics is increasingly showing that at least at the quantum level physical distance between two isolated entities means nothing.

So here is the crux of the problem. In law we need to do justice to peoples’ legitimate claims of assault and abuse. But such claims are inevitably based on concepts that are actually quite ambiguous and slippery.

One of the ways that the law gets around this problem is to assert that bodies are entities with solid, fixed boundaries, so that I can definitively say when “I” have been touched by "you". I can show, for instance, that my skin is sovereign territory that can, at least legally, cannot be breached without my consent.

But as the law is increasingly finding out, such concepts or anything but black-and-white.

Which brings me back to the work I've been doing for the last few years on the philosophy of the physical therapies.

What's becoming increasingly clear is that even those concepts that my profession has always taken for granted as being immutable and absolute are anything but.

It promises to be an interesting year ahead.

Reference

Kleinherenbrink, A. (2018). Against Continuity: Gilles Deleuze’s Speculative Realism. Edinburgh University Press.

Excellent article! If we considered air as a permanent medium for contact, everything would be touching everything at all times, thereby diluting the very concept of “touch.” However, when we intentionally blow or spit, we introduce a dimension of agency and direction that can indeed constitute meaningful (and potentially aggressive) contact in legal and philosophical terms.

Thanks Dave for this interesting approach to touch, I enjoyed the legal considerations. An ethical look raises many questions as well, including unwanted touch in therapeutic settings. What do we touch when we touch?