Between February and May 2023 I wrote six long ‘Stackposts on the theme of posthumanism. I’ve collated them here into one compendium for ease of reading.

I’ve removed all of the decorative images but left the substantive ones in place, and assimilated the references into one long list at the foot of the article.

What is it about posthumanism that’s so appealing?

Firstly, posthumanism feels like it could be a powerful response to many of the anthropogenic problems we’re facing in the world today; most notably the exploitation and enslavement of the earth and its people for the personal gain of a few.

But also because people in healthcare are staunchly humanistic. Whether we come to healthcare with Enlightenment values of objectivity, experimentation, and human sovereignty over animals, plants and inorganic ‘things’; existential beliefs about reality mediated entirely by human subjectivity; or social forces defining the conditions we are born into and live with despite our much-vaunted ‘agency’, our ontological and epistemological presuppositions are deeply anthropocentric.

Western healthcare begins and ends with the human.

Consider this paragraph as an example, from the opening of a recent Guardian review of Ashley Ward’s new book Sensational: A New Story of Our Senses;

’”If you are ambitious to found a new science, measure a smell,” said Alexander Graham Bell to a graduating class in 1914. A century later, scientists are still working on it. But it’s not just smell that remains difficult to define and categorise. Humans can calculate pi to trillions of digits, but can we agree on what the colour teal is? Or whether coriander tastes nice? Or when pleasant stroking becomes annoying tickling? The mildly unnerving point is that much of the information we learn through our senses cannot be objectively measured. Colour “doesn’t actually exist outside of our brains … there is also no sound, or taste, or smell … it’s the brain that construes them” (Guest, 2023).

The unstated assumption here is that sensations are human faculties, created in the brain, with perhaps even no physical basis — or at least, one that eludes (human) science.

An anatomist would no doubt disagree. Are Guest (the reviewer) and Ward (the author) arguing that Golgi tendon organs and post-synaptic channel receptors are present only in human imagining? Or that people of colour also only exist in the minds of individual human beings? I doubt it. And yet the assertion is that it’s the brain that construes sensation.

So what of the vast trillions of entities throughout the universe that do not possess a human brain? Does colour exist for them? Does touch?

If not, and we want to preserve notions like colour and smell only for humans, we need a new structure to our language: one that can accommodate the fact that plants can perceive light to a much higher degree than humans, and bacteria show empathic responses to each other in the presence of noxious chemicals (Chamovitz, 2012).

The problems with our latent and unacknowledged humanism don’t just end there because it’s not just a general notion of ‘the human’ that is used in healthcare, it’s a very specific one. It’s a human that is bounded and autonomous; a human with a distinctive identity; a being with clearly defined spatial edges, and a temporal story running linearly from birth to death.

This is the human taught to us in anatomy and physiology. It’s the elderly woman who falls and fractures her wrist. It’s in the psychology of identity and narratives of illness as a ‘disrupted biographies’ (Engman, 2019). It’s the presumed basis of human relations: of the “I” and the “you”. And it’s in the division between the real and virtual world of simulation and telemedicine.

But how fully encapsulated is this human being really?

Imagine an oxygen molecule somewhere in the room near to you. At some point in the next 10 minutes you’ll breathe that in. But at what point does the oxygen molecule become part of you? When it’s in the trachea? The alveoli? The mitochondria?

Given that about 60% of your body mass — more even than carbon — is made up of oxygen, it has a pretty important role to play in constituting what and who you are, so it would be good to know.

And if, to paraphrase Tim Morton, there’s a lot less of ‘me’ involved in me existing than I’d like to think there is (Morton, 2017), how confident can I be in the classical idea that I, Dave, have a distinctive body, personality and being?

The vast majority of the bounded body that makes up the human being is inorganic matter that is constantly interchanging with the rest of the universe. So do I extend out from my home in New Zealand to include the oxygen molecules just being produced by algal blooms in the swamps of Louisiana?

Where do I begin and the rainforests end?

So is everything just matter?

And if it is, how do we account for the vital force that animates life and differentiates a rock from a child, a dead cat from the one that’s just ruined our curtains?

Would a renewed acknowledgement of the role that matter, objects, forms, and things play in health and healthcare be enough to constitute posthumanism? If so, isn’t this, to paraphrase Foucault, just replacing one bad human-centred hegemony with another (one in which we’ve successfully ‘flattened’ the human but have nothing to say about human affairs)? Does human subjectivity and sociality have any part to play in posthumanism?

These questions have energised a whole new field of philosophy in recent years. And posthumanism has become ‘an umbrella term’ (Ferrando, 2019) to encapsulate a range of loosely related philosophical, cultural, and critical positions, including;

Transhumanism (in its variants as Extropianism, Liberal Transhumanism, and Democratic Transhumanism, among other currents); New Materialisms (a specific feminist development within the posthumanist frame); the heterogeneous landscape of Anti-humanism; the field of Object-Oriented Ontology; Posthumanities and Metahumanities’ (ibid).*

I would argue that if we’re going to make our way through this mass of philosophical complexity, we are going to need a philosophy on which to ground our thinking that is adequate to the task: one that can imagine healthcare in an expanded field.

The biosciences can’t do it alone because they cannot account for human subjectivity and socially constructed knowledge.

Experiential, existential and phenomenological philosophies can’t do it alone either because they have no place for mind-independent entities like sarcomeres and oxygen molecules.

And philosophies of social construction and structure exclude both individual biological, psychological and subjective interpretations of reality.

Pragmatic, ‘holistic’ and whole-world approaches like the biopsychosocial model can’t do it because they remain only superficial, lacking the capacity to overcome the deep ontological differences between their different domains (the biological only sits comfortable next to the psycho and the social in a Venn diagram).

Enter Gilles Deleuze.

To my mind, Deleuze’s radical philosophy might just offer the best way to make sense of all of this. But it cannot be approached from where we currently stand, deeply nested within Enlightenment humanism.

Deleuze operates in a different universe to the world of Western healthcare.

Disinterested in the classic western binaries between true and false, healthy and sick, mad and sane, able-bodied and disabled, human/non-human, Deleuze sets them all aside and constructs an entirely new map with language and concepts that are, at times, completely alien but nonetheless thrilling and enlivening.

*It’s perhaps worth remarking here that I view transhumanism as very different to posthumanism and don’t agree with Ferrando that they should be placed alongside one another. They sound similar, but transhumanism is broadly the pursuit of a more perfectible human, often with the use of techno-scientific adaptations (prostheses). Posthumanism, by contrast, is fundamentally about holding humans to account for our hubris, reducing the dominance enjoyed by humans in our philosophies, and de-centring them when we think about the real life. So while they both have an interest in a broader idea of what matters, transhumanism is much more in line with the Enlightenment ideal of the human as singular ‘man’.

Remember that if the devilwants to kick somebody, he won't do itwith his horse's hoofbut with his human foot

From the poem Pig Roast by Tadeusz Róźewicz (tr. from Polish by Joanna Trzeciak)

In this ‘Stackpost I want to try to tease apart some of the similarities and differences between the main branches of posthumanism, because it’s a relatively new and fertile field, and is already made up of some strikingly diverse philosophies.

To begin with, clarifying some important terms

Firstly, posthumanism does not refer to the ‘death’ of the human in the way that the word posthumous does, but rather the active de-centring of human identity, voice, presence, and aspirations from our thinking, our work, our research, and our practice.

The fact that we are trying to suppress the anthropocentrism of ‘our’ thinking here assumes that the human will always remain somewhere in the picture. The extent to which humans are displaced, however, has allowed for enormous theoretical and methodological creativity.

Transhumanism vs posthumanism

In the crudest sense, transhumanism works in the opposite way to posthumanism.

Transhumanism is a philosophical movement that seeks to enhance, rather than de-centre, human capabilities through the use of technology and science. Its goal is a more perfect human; an ‘ultra-humanism’ (Onishi 2011), through ‘existing, emerging, and speculative technologies (as in the case of regenerative medicine, radical life extension, mind uploading, and cryonics)’ (Ferrando, 2019 p.3).

Its dominant form — Libertarian transhumanism (LT) — draws heavily on Enlightenment ideas of human autonomy and sovereignty, and it aligns politically with free-market thinking and the individual’s freedom to use technology as they see fit.* (See this and this as recent examples).

A second branch of transhumanism is somewhat closer, politically at least, to posthumanism. Democratic transhumanism (DT) is concerned with social justice through the collective distribution of technologies that might bring about a more equitable society. I find it quite hard to distinguish DT from any technological intervention designed to address social inequity though, be it water sanitation in low-income countries or iPads in the classroom. So much depends here on the specific meaning used to designate an intervention as ‘technology’.

DT does share an interest in some of the key questions at the heart of posthumanism, however: questions about the nature of agency, bodies, creativity, identity, and the possibilities for social change. And this overlap has created some understandable confusion, most particularly between DT and critical posthumanism, because both appear to call for a ‘better’ human.

Critical posthumanism and the call for us to do better

Thanks to the work of people like Karen Barad, Jane Bennett, Rosi Braidotti, Judith Butler, Elizabeth Grosz, Donna Haraway, Katherine N. Hayles, Luce Irigaray, Pramod Nayar, Margrit Shildrick, and Isabelle Stengers, critical posthumanism (CP) is by far the most advanced and fleshed-out form of posthumanism to date.

Consider these two quotes which fall squarely within the frame of CP:

‘Posthumanism provides a philosophical foundation from which to shift nursing attention away from its predominant focus on the promotion of ‘human freedom’, human health, human rights and ‘person-centred care’. It helps surface the interrelatedness of humans and the roles of human-centric worldviews in systems of oppression including colonialism, racism, species extinction and climate change (Cohn & Lynch, 2018; Dillard-Wright et al., 2020)’ (Adam et al, 2021)

‘My attention to the operations of difference in posthuman relations aligns with Lucy Suchman’s warning that theories of mutually constituted humans and artefacts must not overlook the persistence of asymmetries in intra-active becoming. As she argues, ‘we need a rearticulation of asymmetry…that somehow retains the recognition of hybrids, cyborgs, and quasi-objects made visible through technoscience studies, while simultaneously recovering certain subject–object positionings – even orderings – among persons and artifacts and their consequences’ (DeFalco 2020)

With their emphasis on the interrelatedness of all things alongside the ‘persistence of asymmetries in [our human] intra-active becoming’ (Adam, et al, above), critical posthumanisms retain the spirit of critical theory while embracing the possibilities for the more-than-human world.

But in attempting to do this, CP exposes a tension at the heart of all of the posthumanisms: the extent to which we should be trying to either mute the human voice or make it sing more in tune.

In CP the goal is the latter, and the language some authors are now using to navigate the subtle complexities of this positioning can range from the elegant and inventive to the complex and obscure:

‘Posthumanism provides a theory of the subject demanding a disruption of the human story as exceptional and considers: what are mediated bodies capable of becoming?’ (Malone & Tran, 2022).

‘A neo-materialist vital position offers a robust rebuttal of the accelerationist and profit-minded knowledge practices of bio-mediated, cognitive capitalism. Taking ‘living matter’ as a zoe-geo-centred process that interacts in complex ways with the techno-social, psychic and natural environments and resists the over-coding by the capitalist profit principle (and the structural inequalities it entails), I end up on an affirmative plane of composition of transversal subjectivities’ (Braidotti, 2019).

There is a subtle shift here from ‘humanistic approaches to practice that focus on humans’ — a ‘relational materialism’, if you will — ‘and their practices and posthumanist approaches that, instead, focus on the very process of connecting, in which all mobilized elements achieve agency through their connections’ (Parolin, 2022).

This approach ‘suggests the displacement of the human subject as the central seat of agency’ (ibid), without, necessarily, insisting upon it.

This approach has been an enormous source of methodological innovation in recent years, and journals like Qualitative Inquiry have been enthusiastic advocates for its exploration.

The case for us to do better

The case for critical posthumanisms are relatively straightforward. Braidotti summarises it this way;

‘[T]he ‘human’ – which so preoccupies legions of thinkers and policy-makers today – never was a universal or a neutral term to begin with. It is rather a normative category that indexes access to privileges and entitlements. Appeals to the ‘human’ are always discriminatory: they create structural distinctions and inequalities among different categories of humans, let alone between humans and non-humans (Braidotti, 2013, 2016)’ {Braidotti, 2019, #134624}.

In plain terms, we could say that for much of human history, perhaps as far back as the pre-Socratic philosophers, humans have seen themselves as superior to all other things in the cosmos, and have increasingly sought to justify this exceptionalism on the basis of human consciousness, reason, and self-awareness.

This accelerated dramatically after the Enlightenment, whose central purpose was to show that ‘man’ was a sovereign, autonomous being with a distinct identity.

Posthumanism sees two major problems with this pyramid of human exceptionalism. Firstly, it perpetuates the belief that humans have a right to think of the world and all its inhabitants this way. Who said, for instance, that consciousness — however we define it — should be the metric that governs universal dominance in the first place? Why not longevity — in which case mountain ranges would probably be at the top? The ability to decompose lignin, Or some other function?

Of course, we did. Humans did. Because we value those capacities most that allow us to think this way in the first place.

But with that sense of exceptionalism comes hubris. And posthumanists are quick to remind people that our belief that the world can be turned to human flourishing has caused us to drive species to extinction, destroy entire ecosystems, strip mine the land, and pollute the oceans. The climate crisis is the poisoned dividend of our human progress.

The second problem posthumanists point to comes from the fact that human hubris does not only extend to other non-human entities, but lives within humanism itself.

The top portion of the gold-coloured pyramid in Figure 1 is not a uniform grouping. The history of human ‘civilisation’ has always been one of privilege for some, and marginalisation for others.

‘[T]here exists no portion of the modern human that is not subject to racialization, which determines the hierarchical ordering of the Homo sapiens species into humans, not-quite-humans, and nonhumans’’ (Weheliye 2014, cited in DeFalco, 2014 p.8)

And while that sense of privilege for some has brought phenomenal progress in science and the arts, it has also been the direct cause of the holocaust and repeated acts of genocide, war, torture, human enslavement, patriarchy, child labour, and sex trafficking, it has fed human greed and placed untold wealth in the hands of very few at the expense of most others, and it has come to define our politics, our culture, and our beliefs about how we relate to others — human and more-than-human — in the world.

‘[W]e might be at the top by force’, Lucy Jones reminds us, but we would be wise to remember that when it comes to everything else that exists in the universe, we are decidedly ‘not at the center’ (Jones, 2023).

It’s also worth bearing in mind that posthumanism holds the political ‘left’ to account for this human hubris as much as the ‘right’;

‘The reinvention of a pan-human is explicit in the conservative discourse of the Catholic Church, in corporate pan-humanism, belligerent military interventionism and UN humanitarianism. It is more oblique but equally strong in the progressive Left, where the legacy of socialist humanism provides the tools to re-work anxiety into political rage. In all cases, we see the emergence of a category – the endangered human – both as evanescent and foundational’ (Braidotti, 2019).

But, we should ask, would things be better if we inverted Fig. 2 and reordered human relations to put majoritarian culture on top, like this?:

In one respect, this would be an entirely justifiable project (and one to which many many people are committed — especially in healthcare).

But this still leaves us with an “us” and “them’ binary which, can only be sustained if one group secures dominance over another. Which always leaves open the possibility for a contest between ‘my’ right/might and your right/might. And ‘freedom for the wolves has often meant death for the sheep’ (Lyons, 2019).

So a third branch of posthumanism focuses on pursuing an even more radical posthumanism; one that deconstructs not only human hubris, but the entire project that makes human hubris possible in the first place; a philosophy based not on the pursuit of a better human being, but one that uses posthuman philosophy to imagine an entirely unremarkable human in a cosmos of wonder.

Radical posthumanism

Just dwelling for a moment on the fact that there are more atoms in a single drop of water than planets in the known universe, should be enough to make us realise that even though the scale of our impact on the planet far outweighs our contribution to its mass, a concern with human exceptionalism is not enough.

We need an approach that can, if only in theory, dissolve away the notion of ‘the human’ as an autonomous, bounded entity altogether.

After all, as I pointed out in the first part of this series on posthumanism, there is a lot less of ‘me’ than humanism would like to acknowledge;

‘not only is the line between human and non-human impossible to definitively draw with regard to the binding together neurophysiology, cognitive states and symbolic behaviours, the line between ‘inside’ and ‘outside’, ‘brain’ and ‘mind’, is also impossible to draw definitively. For the ‘human’, what makes us ‘us’ – whether we are talking about cultural and anthropological inheritances, tool use and technologies, archives and prosthetic devices, or semiotic systems of all kinds – is always already on the scene before we arrive, providing the very antecedent conditions of possibility for our becoming ‘human’. In a fundamental sense, then, what makes us ‘us’ is precisely not us; [emphasis original] it is not even ‘human’ (Wolfe, 2018, p. 358)

And if we could truly revolutionise our thinking about the way entities, including ‘us’, form, deform, and die, then everything is on the non-essentialised table.

The pure sciences, of course, have followed this path for centuries, but they suffer from what Graham Harman called a tendency to undermining — meaning a tendency to reduce everything down to its smallest possible active component. (Here, again, we have the inherent transcendentalism of science — the search for the ultimate fundamental ‘particle’ that forms the basis of all matter).

Similarly, the cultural, social, and political sciences cannot account for the sheer teeming abundance of creativity at play in the world because of their tendency for overmining — reducing everything to its largest super-structural unit (economy, race, gender, etc.).

There has been no shortage of interest in this kind of radical philosophical speculation in recent years, particularly from people like Ian Bogost, Franz Brentano, Levi Bryant, Manuel DeLanda, Tristan Garcia, Graham Harman, Bruno Latour, Quentin Meillassoux, and Tim Morton.** And their work draws on a rich heritage, including various aspects of the philosophies of Nietzsche, Foucault, Husserl, Heidegger, Leibniz, Spinoza, and Whitehead.

But many see Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari as the crown princes of radical posthumanism, in part because their work displaces all of the parameters of conventional (Western) philosophy and creates a new approach to thinking that, while it still holds relevance for human studies, makes possible an analysis of people as just one entity among billions;

‘At this present moment in intellectual history it is impossible to consider the human without contextualizing it with the nonhuman turn. Furthermore, it is unsurprising that the nonhuman turn has been, in its entirety, an interdisciplinary affair – no discipline has a unique purchase on the nonhuman, and engaging with it demands of us that we exceed the boundaries set before us. As does Deleuze. Indeed, there is no single thinker who occupies the nexus of so many intersecting lines’ (Roffe and Stark, 2015).

Radical posthumanism, of course, has its own problems. Not least being the question of how one practically, methodologically, even theoretically, removes oneself from thinking, researching, and practicing enough to do justice to the idea of a radically de-centred human? Aren’t you always already there?

Is Braidotti right to argue that;

‘One needs at least some subject position: this need not be either unitary or exclusively anthropocentric, but it must be the site for political and ethical accountability, for collective imaginaries and shared aspirations’ (Braidotti, 2013 p.102)?

And even if it were possible to become that minoritarian, is there not the sense that doing this work is not enough in the face of structural racism, patriarchy, social injustice, rampant capitalism, and an impending climate catastrophe?

In the next post I’ll try to tackle some of these questions and give some thought to the core principles of posthumanism, before moving on to some ways we might think about this in healthcare.

As always, I truly value your thoughts and comments on any of this.

This is a work of discovery for me and I’m using this writing very much as a way to work through how I can used these ideas in the future.

So, if you have anything you’d like to add to this melange, it would be lovely to hear from you.

Footnotes

* Examples of LT can be found in the work of people like Max More, Nick Bostrom, Aubrey de Grey, Natasha Vita-More, and Anders Sandberg.

** If I were a poststructural feminist, I might be tempted to point out that the vast majority of critical posthumanists are women, whereas those in a radical ‘anti-humanism’ are almost exclusively men. Equally;

’The ‘newness’ of new materialism is relative only to Western/Eurocentric ontology: its recognition of continuities between natural and social worlds recapitulates aspects of indigenous and First Nation ontologies (Rosiek et al., 2020; Sundberg, 2014). Braidotti (2022: 108) suggests ‘renewed materialism’ as a more apt nomenclature terminology). For critical assessments of the new materialisms, see Lettow (2017) and Rekret (2018)’ (Fox, 2022. See also Warbrick et al, 2023).

Or, to quote Rosi Braidotti, ‘when it comes to human/non-human relations, it is time to start learning from the South’ (Braidotti, 2020 p.467).

Perhaps the salient point here is that these arguments sit firmly within a critical posthuman frame. You are unlikely to see a radical posthumanist making this argument, because they would reject the notion of any essentialised human that critical posthumanism bases its posthumanism upon. To quote Foucault;

‘nothing in man — not even his body — is sufficiently stable to serve as the basis for self-recognition or for understanding other men’ (Foucault 1977).

”If you desired to change the world, where would you start? With yourself or others?” - Alexander Solzhenitsyn

Introduction

In this third part of this series on posthumanism (Part 1 and Part 2), I had intended to define some key principles for thinking with posthumanism. But as I worked on that piece, I found I needed to be clearer about my own philosophical orientation, so that I didn’t give the impression that my list of key principles could be seen as definitive. Posthumanism is a wide discipline covering diverse philosophical orientations, and some of these are about as far apart ontologically as you can get.

Graham Harman’s Object Oriented Ontology is dismissive of Karen Barad’s agential realism (as we will see below). Ray Brassier’s nihilism is the polar opposite of Arjen Kleinherenbrink’s life-affirming Deleuzian machine ontology. Manuel DeLanda’s assemblage theory is realist while David Lapoujade’s aberrant movement is not. Rosi Braidotti’s nomadic subjectivity has nothing to say about Tristan Garcia’s form and object. And while Tim Morton’s hyperobjects bear some similarities to Donna Haraway’s cyborg hybridity and Luce Irigaray’s vegetal being, Erin Manning’s relationscapes, Jane Bennett’s thing-power, Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory, and Thomas Lemke’s governmentality of things, all strike out in notably different directions.

Given this dizzying array of posthuman philosophies, it is perhaps understandable that authors try to narrow things down a bit, as Rebekah Sheldon has done by suggesting that;

‘Within this broad and interdisciplinary movement, two methods have attained particular visibility: speculative realism, especially object-oriented ontology, and new materialism, especially feminist new materialism’ (Sheldon, 2015, p. 193).

I think there’s some merit in offering this binary, not because it defines a difference between approaches based on gendered identity politics, but because it highlights some important ontological and epistemological differences that anyone coming into posthumanism would be wise to wrestle with. So let’s take a moment to unpack the two sides Sheldon highlights.

Speculative Realism and New Materialism

In the footnotes to Part 2 of this series, I commented that “If I were a poststructural feminist, I might be tempted to point out that the vast majority of critical posthumanists are women, whereas those in a radical ‘anti-humanism’ are almost exclusively men” (link). Well, Rebekah Sheldon makes the same point in her excellent overview of the problems critical feminists have with speculative realism (Sheldon, 2015).

Writers like Graham Harman, Levi Bryant, Nick Srniceck, and Quentin Meillassoux, she argues, will tell the history of the posthuman turn without even mentioning women like Stacy Alaimo, Karen Barad, Jane Bennett, Rosi Braidotti, Judith Butler, Melinda Cooper, Elizabeth Grosz, Donna Haraway, Valerie Hartouni, N. Katherine Hayles, Myra J. Hird, Luce Irigaray, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Annemarie Mol, or Celia Roberts.

’The absence of women from this story of succession is remarkable both for its casual and apparently unwitting embrace of patrilineation, but also, and more incisively, for the distortions it relies on to produce such a clean line of descent’ (Sheldon, 2015, p. 203, see also a similar comment by Lemke, 2021, p.38).

In effect, speculative realism (SR) and Object Oriented Ontology (OOO) have relegated critical posthumanism to a footnote ‘within its own autobiography’ (Sheldon, 2015, p.204).

But this ignorance, Sheldon argues, only masks a deeper ontological dismissal of the critical problems that motivated the critical posthuman turn in the first place. Simply put, SR and OOO say nothing about ongoing oppression and, in their dismissal, enable or even perpetuate it.

Feminist new materialism (FNM), which has become the fulcrum around which a great deal of critical posthumanism turns, broadly argues for:

A critique of scientific neutrality;

The role of culture in mediating between things and our experience of them;

The non-discursive agency of other-than-human forces (Hird & Roberts, 2011);

Human critical humility, and an accompanying respect for the ‘vivacity, vulnerability, and sometimes… surly intransigence of nature’ (Sheldon, 2015, p. 195).

But perhaps the defining feature of FNM is its focus on the direct material consequences of human knowledge systems. Epistemology for feminist new materialists is ‘emphatically relational’ (Sheldon, 2015, p. 195), hence why, Sheldon argues, feminist theorists use so many phrases with double articulations; phrases like nature–culture, material–discursive, and intra–action. Reality is constituted by the interplay of ideas and things. Entities are defined both by their ability to affect and be affected by others: what Fox and Alldred called an ‘affect economy’ (Fox & Alldred, 2016).

OOO, by contrast, sees entities as having a mind-independent reality, but also a reality that is fundamentally inaccessible. No entity can ever be fully exhausted by its relations. Following Heidegger and Husserl, Graham Harman — one of the chief proponents of OOO — argues that all entities share the same fourfold structure with surface effects that objects encounter when they interact, concealing an ontologically withdrawn ‘core’.

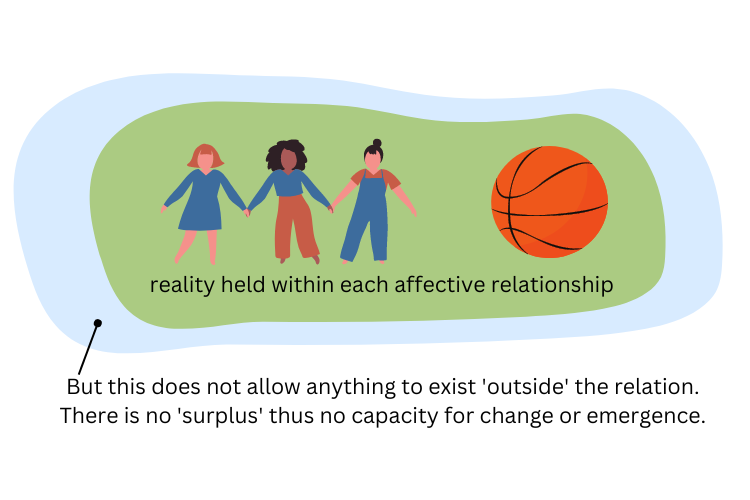

OOO argues that the concept of an affect economy fails on two counts: firstly because it cannot explain change; because if everything that exists is encompassed by the relation between entities, there can be no surplus: no potential for anything new to emerge beyond the boundary of the two entities in relation. If theories of affect (a key feature of FNM) did allow for a zone of indeterminacy outside of the affective relation, then reality cannot be explained by affect alone, as its proponents suggest. So, in the eyes of speculative realists, affect fails because it cannot explain change or emergence.

But affect also fails because it cannot account for a mind-independent reality. Kantian philosophy encouraged us to believe that the world only came into existence with the arrival of a mind that was sophisticated enough to conceive it. FNM argues exactly this: that our knowledge of the world is fundamentally a learned act; that ‘experience and ideation emerge out of structures of knowledge’ (Sheldon, 2015, p. 200). More than this, though, FNM argues that these structures are defined by historical discourses of sex and gender (ibid).

There is a turbulent political dispute here then, with FNM advocates arguing that SR and OOO theorists are engaged in ‘the seemingly never-ending process of pushing back against new, creative ways to suppress emancipatory project(s)’ (ibid), while realists like Manuel DeLanda ungraciously argues that “I have even more contempt for those who appeal to the worst parts of science - such as [Karen] Barad” (DeLanda & Harman, 2017, p. 7).

Sheldon is perhaps right then to suggest that the relationship between SR and FNM is ‘particularly rancorous’ (Sheldon, 2015, p. 194);

’The antagonism between these two fields is in some ways easily understood. After all, feminism is historically constituted around human subjectivity, sexed specificity, and the sculpting effects of culture. Add to that the origin of feminists’ engagement with the sciences in a critique of scientific neutrality—a critique that argues quite precisely for the intercalation of culture between things and our experiences of them—and it becomes clear why the two fields have been wary of each other’ (Sheldon, 2015, p. 195).

In Sheldon’s view, the dispute between these two main branches of posthumanism recapitulates;

‘the hoariest of philosophical binaries: the form/matter distinction’ (ibid), in which OOO privileges form as an aloof, detached, non-agential entity – akin to the classical notion of one’s sex, where FNM is concerned with matter and the dynamic, mobile, and fluid notion of nonhuman agency - akin to the contemporary reading of gender’ (ibid).

And given what is at stake, it is perhaps understandable that a new wave of poststructural feminists are eager to hold on to the emancipatory drive of the past whilst, at the same time, opening new critical lines of flight.

Susan Bordo recently made the stakes clear;

’Since the election of Trump, preceded by a misogynist campaign that was shocking in its hostility and followed by the stripping away of rights we’d counted on for 50 years, it’s become clearer and clearer that we are far from “post” feminism’ (Bordo, 2023).

On the surface, it would seem that a crucial point of difference between FNM and SR lies in the way they relate to the human. In FNM relations precede ‘being’, but it is this being-in-relation that then brings about new relations. Barad calls these intra-actions, with matter and discourse co-constituting one another. Besides Karen Barad’s Meeting the Universe Half Way (Barad et al., 1996), there are also some excellent examples of this in Annemarie Mol’s The body multiple (Mol, 2002), Myra Hird’s The origins of sociable life (Hird, 2009), and Stacy Almao’s Bodily natures (Alaimo, 2010).

There is little doubt, though, that FNM explicitly retains a place for the human because, ultimately, it wants to offer new modes of critique for the kinds of oppression and marginalisation that feminism has fought against for aeons. In this sense, then, it struggles sometimes to identify in what ways it is post-human.

OOO by contrast, appears to be entirely nonhuman, making no apparent effort to single out the human from any other entity in its radically flat ontology. SR and OOO recognise matter only as a ‘fixed, flat, or law-like substrate’ (Bennett, 2015, p. 233). Harman even goes as far as to say that “Any philosophy that is intrinsically committed to human subjects and dead matter as two sides of a great ontological divide…. Fails the flat ontology test” (DeLanda & Harman, 2017, pp. 85-86). Humans are merely one entity among a universe of others.

And yet, the sheer strangeness of objects that SR celebrates, resurrects a ‘blunt form of subjectivism that not only remains within the humanist frame but is also distinctly gendered’ (Taylor, 2016, p. 210). Who is it, Carol Taylor asks, that renders the ‘alien’ object knowable? By whose criteria is this rendering deemed to be ’satisfactory’ (ibid)? Tellingly;

’the human who is reinstalled as recorder of traces is indubitably male, embodying an opaque set of values, and judging from a distance’ (ibid).

From a critical posthuman standpoint, SR and OOO make no attempt to link the differential power of humans to nonhuman objects;

’at the very moment when humans have caused a state shift in the earth’s biosphere and are presiding over a mass extinction, we are witness to the ascendency of a social theory that massively redistributes agency to the nonhuman and promotes withdrawal as the primary mode of being’ (Campbell et al., 2019, pp. 129-130).

The politics of posthumanism

Clearly then, the battle for the soul of posthumanism is a deeply political one, especially when it comes to critical posthumanism.

But herein, for me, lies one of its weaknesses, because it is sometimes hard to see what it offers to critical questions of anthropocentrism, patriarchy, rampant capitalism, human exploitation, and alienation that is not already there in the critical theory literature. Critical posthumanism bears some striking similarities to intersectional theory, but perhaps with greater attention paid to the mattering of things. It remains, however, a project fundamentally underpinned by an orientation to human social life.

And there is nothing wrong with this. The more tools we can have that bring about critical change the better. But these tools have so far proven to be only partially successful, as Susan Bordo suggests above.

For me, the real promise of posthumanism lies in its ability to break the gravitational pull of the earth and break the long history of human-centred thinking that has beset thinkers in the West for centuries. In doing so, I believe posthumanism offers the promise of some really radical ideas for future life for all.

Perhaps the most emotionally challenging advocate of this radical approach to posthumanism is Ray Brassier, whose nihilism argues that the logical conclusion of the hubristic human search for objective reality will the ultimate destruction of the manifest image of man (Brassier, 2007). But rather than seeing this absolute nihilism as a depressingly hopeless image of the future, Brassier argues that if we can get past the idea of our own extinction, we might be better placed to understand the full extent of thought as it exists already, beyond the boundaries of our anthropocentrism.

In many ways, it’s a powerful way to help us break our tendency to think like humans, but it fails on two counts: firstly, because it bears many resemblances to ancient stoic and skeptical philosophy in which it is wisdom, not destruction, that results from our rejection of our humanism; and secondly, because rather than engendering a cosmic nihilism, an ultimate form of subjective idealism might be the result of stripping away our human qualities, because all the Ego would be left with would be knowing ‘nothing but itself and its own ideas’ (Woodward, 2015, p. 33).

And this, for me at least, is where Deleuze’s philosophy of life comes into its own, because Deleuze sees ‘life’ as a motive force within all things: as an animating, dynamic, creative energy that is the expression of ‘ineliminable difference on the basis of an absolute univocity of being’ (Roffe, 2015, p. 43). In other words: every entity is unique in its difference; encounters with other entities are the engine of creativity; every encounter creates a new ‘third’ entity that shares the same univocal structure as its progenitors, but is unique in its qualitative difference; and that this repetition of difference means that the cosmos is in a constant process of becoming, never stabilised sufficiently to constitute static ’being’.

What will follow in the next post will be a set of key principles that might, just might, allow us to break the gravitational pull of the earth and allow us to develop radically new ways to think about health and healthcare, not as person-centred disciplines, but as philosophies for all kinds of new becomings.

Apologies again for the lengthy diversion, but it felt necessary to set this debate down before pushing on.

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts, comments, challenges, and questions. So please add comments below and pass this post on to anyone you think might be interested.

Having set out my own position among the different schools of posthumanism in Part 3 (link), I thought I should probably now lay down the key principles that follow from this, and then I can try to explain how I apply them to healthcare thinking and practice — my methodology if you will — in the next installment.

Before we begin, I offer you a mea culpa for some of the pretty heavy theory that is littered throughout this post. Condensing controversial arguments and radical alternatives into one readable blog post is never easy. I hope it doesn’t spoil your enjoyment of the piece.

If the philosophy does get too much for you, though, here’s a potted version of the arguments laid out in this post:

Human exceptionalism, notions of identity and ‘being, transcendentalism, and discovery are ubiquitous and hugely problematic both in Western society in general and healthcare in particular. Wherever we find them, we should try to root these out and replace them with Deleuzian posthuman philosophies of becoming, immanence, and creativity. These speak directly to the joyful pandemonium that is life and so are much closer to what’s really going on.

So let’s take each of these in order.

1. Against human exceptionalism

This is perhaps the obvious first principle of posthumanism, and I’ve covered some of its main forms in the last three posts. To briefly summarise, as Christine Daigle and Terrance McDonald recently wrote, ‘The idea that we must overcome humanist thinking, its dualistic stance and concomitant human exceptionalism is at the core of critical posthumanism’ (Daigle & McDonald, 2023).

We are talking here about different forms of de-centering, from contextualising the human within the context of the nonhuman turn (Stark & Roffe, 2015, p. 2), to a more complete and radical nonhumanism (see Brassier below).

Regardless of the outcome of this work, the starting point is often an ‘intense and harsh critique of classical philosophical understandings of the human as separate from nature and other beings, and of the human as superior to other beings in virtue of possessing reason’ (Daigle & McDonald, 2023).

But just as there is a general opening towards the more-than-human in posthumanism, there is, at the same time, an important political critique in play, particularly where some would embrace a worldly pan-humanism as a veiled way to reify the place of humans at the centre of the universe. We see this most often in what Rosi Braidotti called the ‘endangered human’ narrative;

‘The reinvention of a pan-human is explicit in the conservative discourse of the Catholic Church, in corporate pan-humanism, belligerent military interventionism and UN humanitarianism. It is more oblique but equally strong in the progressive Left, where the legacy of socialist humanism provides the tools to re-work anxiety into political rage. In all cases, we see the emergence of a category – the endangered human – both as evanescent and foundational’ (Braidotti, 2019).

So posthumanism is as disparaging about the humanitarianism of socialism, person-centred care, and aid work, as it is about organised religion, venture capital, and transhumanism, when these are covertly underpinned by an ethic of human flourishing.

One way that writers in recent times have tried to make this tendency visible and escape its magnetic pull is through the exploration of nihilism. Chief among these has been Ray Brassier.

Nihilism, since Nietzsche, has offered a powerful critique of dogmatic thought. Some humans, Nietzsche argued, are always looking to the past. Rather than fully engaging in the future, they never allow themselves to forget their pains and old sadnesses; constantly recollecting and dredging the past into the present. Nietzsche called them ‘resentful’ types and ‘slaves’ to their memories.

The seemingly endless rumination drives personal judgment, passivity, identity fixation, and self-blame into the person’s psyche — a force all too easily fed upon by powerful social discourses like science and religion (Nietzsche thought all religions were evil in this regard). Ultimately, the resentful type presents as an outwardly ‘moral’ person, but this person only really ever resents others and yearns to become their ‘hangman’ (Nietzsche, 2001).

The contrast for Nietzsche was the person who acted without resentment: without dragging up the past; always with both eyes fixed on the world to come. They have a lust for life, for becoming; they are ‘masters’, always open to disruption, ambiguity, possibility, emergence, and spontaneity. In Nietzsche’s famous allegory of the demon in the eternal recurrence, it is the übermensch — the joyous, free spirit — that would be happy to live their life over and over again just as it has been lived till now.

Following Nietzsche, Brassier sees Enlightenment science as a powerful force of nihilism. Our four-century-long search to map and measure every facet of human existence, to know the world and bend it to our will, is a project doomed to bring about our psychic and physical destruction (Brassier, 2007). Far from bringing untold social benefits, our modern fetish for reason and logic, taxonomy and diagnosis, and human cures for ‘man’-made problems, will be our undoing.

But Brassier takes a surprising turn here. Rather than siding with Nietzsche, Spinoza, Deleuze, and others in arguing for the possibility of a radical new posthuman view of ‘life’, Brassier argues for death: specifically the possibilities of understanding creation and thought beyond human imagining. Only by embracing our inevitable demise in life will we be able to grasp the other-than-human world more fully.

One of the problems of a lot of posthumanist writing is that it all-too-often struggles to fully escape human ‘being’. It is, as Jane Bennett says, very hard to rid ourselves of our anthropocentrism (Bennett, 2009). But if posthumanism is going to offer something fundamentally different than, say, critical theory has offered in the past, it must work out how to do this. So, perhaps Brassier’s approach is worth considering.

2. Becoming not being

‘nothing in man — not even his body — is sufficiently stable to serve as the basis for self-recognition or for understanding other men’ (Foucault, 1977).

‘Being’ is almost so ubiquitous in Western thinking that it’s hard to imagine a philosophy working in any other way. But posthumanism attempts to do exactly this, by ‘fractur((ing)) the assumed coherence’ of the world (Brown, 2020). Posthumanism takes to task all of those places where ‘being’ is taken for granted, and many of these areas form the very backbone of our work in healthcare:

In science, with its passion for giving names to things through its objective taxonomic, diagnostic clarity, such that we take for granted seemingly ‘solid’ forms of being like ‘the body’, ‘the mind’, and ‘disease’, and with them, the necessary correlates of ‘reason’, ‘logic’, ‘objectivity’, and ‘truth’;

In phenomenology and its (inter)subjective ‘being-in-the-world’, which leads to the over-used qualitative question of what it means to ‘be’ someone with Parkinson’s disease, and what being disabled means for you;

In social theory with its socially constructed identities based on ability, ethnicity, gender, and so on; a naming that is necessary to give voice to the marginalised ‘other’;

In the language we use to define concepts and their limits: ‘caring’, ‘therapy’, ‘pain’, ‘nursing’, ‘behaviour’, ‘addiction’, and so on;

And even in recent assemblage theory — a branch of posthumanism associated with Deleuze — with the listing of ‘things’ that can now be brought into consideration when we think about health (air conditioning units, trees, fictional characters in stories, graffiti, etc.), or the hyphenated lists of ‘things’ that now supposedly break with essentialised ideas of ‘being’: the sidewalk-wheelchair-skin assemblage, for instance.

(Of course, the great irony in all of this is my own use of fixed labels to list the disciplines that themselves privilege seemingly fixed identities).

‘Being’ imposes temporal and spatial stability on things. And yet, this is, of course, illusory.

In Deleuzian posthuman theory, being tells us nothing about the boundless, relentless, and unfathomably enormous process of ontogenesis that is at work in the cosmos; a process that expresses the endless repetition of creativity through difference, not sameness, becoming not being.

In keeping with its ethos, becoming may be a harder concept to ‘pin down’ but it comes closer to the reality of constant cosmic creation, conatus, and collapse than fixed identities and endlessly contested labels ever will.

’It’s not a question of being this or that sort of human, but of becoming inhuman, of a universal animal becoming – not seeing yourself as some dumb animal, but unraveling your body’s human organization exploring, this or that zone of bodily intensity, with everyone discovering their own particular zones, and the groups, populations, species that inhabit them’ (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987, p. 11).

3. Immanence, not transcendence

In a similar way to ‘being’, transcendence penetrates modern thought so deeply that it is hard to imagine thinking without it.

Transcendence refers to the present as a ‘projection’ of some greater or higher realm.

Many religions, ancient and indigenous cultures propose ‘higher’ gods, or some form of ‘other place’ where people go beyond this life. Enlightenment science called this superstition but replaced one form of transcendentalism with another when it argued that there are mind-independent truths and natural laws governing the universe. Plato thought that there were ideal ‘forms’ of everything we experienced in the world — us included — that were merely images of the realm of truth. Moral philosophers suggest that there must be something more to life than mere existence; why else would humans have been blessed with the gift of consciousness and self-reflection? And social theory isn’t immune from transcendentalism either, especially those areas that are concerned with the social structures that exist in the world and give the lie to myths about human autonomy and agency (Marxism and linguistics, for example).

Deleuzian posthumanism following Bergson, Leibniz, Nietzsche, Ruyer, Spinoza, and others, rejects the idea that there is somewhere else, or something else, to which life points. Transcendence is rejected in all its forms, in favour of immanence. In immanence, nothing ever has to go outside to fully realise itself. All it needs is right here.

Key here is the primacy Bergson and Deleuze give to intuition and gnosis — or the most direct, unmediated knowledge of the world — that all entities possess (as opposed to intellect, which always seems to lead to epistemic knowledge, the search for transcendental explanations, and nihilism).

But immanence also provides the basis for radically different concepts of duration (or ‘time’ in the Western canon), space (the ‘surplus’ that exists for all things and makes change possible that does not reside outside in some cosmic waiting room, but is folded into this moment, this entity, this relation), and thought (a more-than-human phenomenon).

4. Creation, not discovery

It perhaps follows from the critique of identity and being that posthuman thinking — particularly of a Deleuzian flavour — would dispute the place of discovery as a mode of thought.

Where Western philosophy has largely been a centuries-long project to discover how we should live (meaning the forms of logic and reason that frame the natural and social laws that are, in turn, sufficient to govern our species-being), posthumanism asks how could we live (May, 2005).

So while the Enlightenment project and all of its many offspring (modern healthcare, health professions and disciplines, clinical assessment and treatment, quantitative and qualitative research, etc.), pursue ever greater forms of discovery, posthumanists argue that we are being increasingly locked in the nihilism of instrumental reason.

In discovery, we see the stain of transcendentalism again because discovery is orientated only towards finding the thing that already exists ‘out there’, beyond our current knowledge. It is a mindset that is already prepared to make sense of what it sees.

But this is not what creates the ‘new’ or explains the sheer ceaseless productivity of the universe. It is the shock of the new, the violence of becoming, and the danger inherent in surplus that is the engine of the cosmos.

As Deleuze says, we are inside a thunderstorm, not a watercolour painting (Deleuze, 1993).

What then do these make possible?

It can be hard to know where to start as a posthuman thinker if we have to abandon even our starting points because they are so much the product of Western Enlightenment thinking. I mean, I’m a physiotherapist by training, interested in what a posthuman reading of bodies, movement, touch, and therapy might offer, but these terms are expressions of a flawed philosophy, so surely I should begin by rejecting all of these concepts and starting somewhere else?

This paradox is nothing new to posthumanism, though. As Hannah Stark and Joe Roffe argued, we are ‘simultaneously contextualized as a minuscule entity in relation to nonhuman time scales’ whilst also ‘positioned as the force shaping a new geological era’ (Stark & Roffe, 2015, p. 5).

I think, though, that Deleuzian posthumanism offers some remarkably creative ways to think if we can first uncouple our humanism and see putatively human practices like care and touch as being not just human interventions, but features of the becoming of all things. Understanding ‘therapy’ as a concept that applies as much to dying leaves as it does to human touch, for instance, is an exciting shift in what had become a rather stale, unremarkable field of thought in recent years.

There is surely more to wound care than just caring for human wounds.

There is also a critical project to be done here and posthumanism certainly provides lots of new tools to expose the often understated anthropogenic and professogenic assumptions underpinning healthcare (Burns, 2019). Much of this critique can be found in the posthuman literature, which has, as yet, been largely ignored by health professionals and those who write on the need for reform.

At its heart, though, Deleuzian posthumanism appeals to me because it aims at ‘the production of joyful or affirmative values and projects’ (Braidotti, 2019). It is a playful disengagement.

‘from the rules, conventions and institutional protocols of the academic disciplines. This nomadic exodus from disciplinary ‘homes’ shifts the point of reference away from the authority of the past and onto accountability for the present (as both actual and virtual). This is what Foucault and Deleuze called ‘the philosophy of the outside’: thinking of, in, and for the world – a becoming-world of knowledge production practices’ (ibid).

Postscript

As I was writing this piece, I read about the death of British sculptor Phyllida Barlow. In a lovely interview with Katy Hessel some years earlier, Barlow said this about the work of sculpture;

“I think the relationship of a warm-blooded creature vs an object that is still and silent – which is essentially what I think sculpture is – for me is the sort of fundamentals. Sculpture is in our everyday lives the whole time. Crossing the road with a lorry coming towards you, is, in my opinion, a sculptural experience, where you as a flesh and blood object is up against the thing that isn't. And one’s emotional and psychological assessment of that all happen in a flash” (Hessel, 2021).

I’m increasingly wondering if posthumanism isn’t a term for the act of sculpture that all things, not just human minds, engage in as a fundamental function of their existence; always seeing it as a chance to create something new.

“What will undo any boundary is the awareness that it is our vision, and not what we are viewing, that is limited” - James Carse

Apart from a final summary of key resources, this will be the last piece in this series on posthumanism. There are a lot more ‘posts’ I want to tackle over the coming months: post-professionalism and post-qualitative research not being the least of these.

But speaking of post-qualitative research, this penultimate post looks at how we might actualise posthuman thinking in research and practice. But to do that, a couple of warning shots need to be fired. The first is that methodology is probably a poor name for this work because it is a term that’s been so corrupted in healthcare research — especially by qualitative health researchers — in recent decades, that it’s come to stand for a pernicious mode of capture that ensnares many novice researchers.

This is how Elizabeth Adams St Pierre recently described her experience as a doctoral student;

‘It was so easy, so clear, so accessible. [Qualitative research methods] told me what to do and when and how to do it. I didn’t have to think. I didn’t need any theory at all, really. I could just get some data and then organize them into themes that appeared all on their own. All I had to do was follow the recipe and then write up my findings. So simple, really, to just be a functionary of the method. So dreadfully boring’ (St. Pierre, 2023).

Qualitative health research has become deeply Cartesian and humanist. It is often mechanistic and instrumental. It privileges discovery and feeds the desire to stabilise ideas around concepts like being and identity. And ‘although it claims to be interpretive, its empiricism leans toward logical empiricism’ (ibid).

It encourages students to focus on which methodology they will choose from the expanding buffet of pre-validated options available to them. I had a student recently advised by a colleague to use autoethnography for a study proposal that the advisor hadn’t even read. Another colleague was told that their faculty would only allow them to use one of five (why five?) well-known and tightly structured qualitative methods for their doctorate.

Philosophy and ontology still remain worrisome words for a lot of health researchers, and the question of which arrangement of ontology and epistemology might form the lifeblood of the study, are often substituted for the desire to ‘choose your methodology and get going’ (ibid);

‘It certainly never occurred to me as a doctoral student that if I began my study with the immanent ontology of poststructuralism I would not think or use a preexisting social science research methodology that is not immanent. If I had actually begun my dissertation research with poststructuralism, I would not have done that interview study at all. After all, in his Archeology of Knowledge, Foucault wrote over and over again that he was not interested in the speaking subject—that he worked in the order of discourse instead. It is interpretive, not poststructural, work that focuses on the voices of people describing their everyday lived experiences. But I just followed the qualitative process I’d been taught like an obliging doc student. I went to the field and interviewed and observed and did all the “empirical” things you’re supposed to do as an empirical qualitative researcher. But the “empirical” I studied was limited to people’s words and what I “observed.” The richness of the empirical could not possibly be captured by qualitative methods’ (ibid).

How, then, might we use the ontological and epistemological approaches set out in the first four parts of this series on posthumanism to frame ways of thinking and practicing without falling back into the cozy but ultimately suffocating recliner of qualitative methodology?

There are clearly some things we should avoid — including prescriptions. So, one way to think about the best way forward might be to think of a set of dispositions that orientate the way we palpate (rather than discover or define) our creations.

Put another way, if I were examining a posthuman thesis, what applied principles would I expect the candidate to base their study around?

Some methodological pointers

Our tendency is to want to understand things spatially — to give everything spatial coordinates, physical form, a defined shape, and mass. We ask where are memories, illnesses, or pains ‘found’ or ‘stored’ in the body. We essentialise entities and fix them in ‘being’. We like identities, images of solidity and permanence: “This is a book”.

But this act of colonisation and capture strips away all of the creative energy that makes the universe the swirling vortex of emergence that it really is.

So while spatial questions are valid in themselves, they have come to dominate almost all the ways we think in healthcare research whilst also obscuring the dynamic power of creativity.

Here’s how Clair Colebrook explains how a spatial attitude shapes how we think about movement;

’We have usually thought of time as the joining up of movement; time is what links, say, each step of my walk into a perceived line or unified action. But we can reverse this and say that time, far from being some sort of glue that holds distinct points of experience together, is an explosive force. Time is the power of life to move and become. Time produces movement, but the error has been to derive time from movement’ (Colebrook, 2002, p. 40).

When we impose spatial concepts on processes that are fundamentally temporal we replace the divergence, becoming, flow, disruption, qualitative difference, plurality, change, intensity, and liminality of duration (time, aeon) with the appearance of linear progression, quantifiable unity, fixity and stasis, likeness, events linked in sequence, order, cause and effect, numbers, homogeneity, and the human fantasy of control (metric space, chronos).

What a focus on ‘duration’ (the term Bergson used to differentiate it from ‘clock time’) allows for, is a focus on movement, flow, and becoming, rather than stasis, being, and fixed identity.

For some, aberrant movement (Lapoujade, 2017) might even be the engine behind all forms of creative life because it is movement that brings entities into relation and, through them, the creation of a new world.

‘Deleuze’s ontology is a rigorous attempt to think of process and metamorphosis — becoming — not as a transition or transformation from one point to another, but rather as an attempt to think of the real as a process’ (Boundas, 2005).

’Intuition is... the movement by which we emerge from our own duration, by which we make use of our own duration to affirm and immediately recognise the existence of other durations above or below us’ (Deleuze 1988, p.33}.

Another important example of the way we can think about time and duration differently comes from Henri Bergson’s challenge to the traditional linear, survival-of-the-fittest narrative of (human) evolution. Bergson suggested that the evolutionary path humans had taken was only one path and that there were as many paths as there were entities in the cosmos. Our path has led us to value reason and logic and to believe that these traits made us exceptional. Our self-appointed exceptionalism then justifies our belief that we were entitled to bend the rest of the natural world to our advantage. But this path was only ever the expression of a particularly competitive, hubristic, and anthropocentric view. Other entities, becomings, processes, and flows will be entirely indifferent to this view, and so have their own expressions of a much more creative evolution; one that does not reduce duration to a set of quantitative measures and rational coordinates.

But how do we as humans access these other becomings, flows, and movements? How do any entities do it? (And here it’s probably worth restating the obvious point that we’re not just talking about other living beings here, even objects and things, but also processes and events, and other incorporeal entities like thoughts, social constructs, and stories.) Deleuze called his own approach to this problem transcendental empiricism (TE).

TE is empirical because it concerns the way all entities encounter the other through signs and manifestations without ever being able to fully capture or know the other, and transcendental because thought (again, not only human thought but that which is necessary for any entities to interact), allows entities to go beyond mere connection or relation to sense the real, necessary, virtual, private interior of the other.

‘The illusion is to think that because we are synthesising machines, that “mind” is therefore the origin of that synthesising activity. In fact, mind is already a synthesis of myriad inhuman encounters. What Deleuze calls “transcendental empiricism” is precisely his attempt to think the genetic evolution of the thinking subject, and to trace lines of potential deviation-transformation’ Link.

It is always tempting to try to make sense of the strangeness of posthuman thought by essentialising the thinking subject and imagining relations in some form like atoms, or billiard balls, or as mind maps with solid entities connected by thousands of intersecting lines. Everyone probably does it, because we’re so socialised to think spatially, not temporally. But, as I suggested above, this confuses a fundamentally creative process of becoming with identity and being. It gives solidity to things that aren’t structural. We see this even in posthuman research, especially in the use of assemblage theory.

Perhaps the idea of assemblages appeals to our mechanistic fantasy of solid entities connecting via invisible strings. The problem is the tendency to reduce assemblages to interconnect things. If all you have is a hand, a hammer, and a nail, then everything looks like a hand-hammer-nail assemblage. But assemblage theory is about processes, not the ‘things themselves’. It is the manifestation of duration, so is about becoming not being, flow not fixity (Buchanan 2020).

Which, of course, forces upon us all kinds of ambiguities and uncertainties. For years now, existential philosophers have examined the ways humans have tried to address what Avital Ronell called the “gash of non-meaning” (see video below).

This ‘gash’ is a part of being conscious sensate beings. We dislike uncertainty and wonder why it is we have these remarkable capacities if there is no higher purpose. So we invent Gods, natural laws, and reason as ways to salve the pain that comes with the realisation of our impotence. Our reaching for “emergency supplies of meaning” (ibid) is used by many as justification for all manner of atrocities in our vain attempt to give meaning to our existence (see Simone Bignall’s fantastic explanation of how men’s existential impotence has been used to inflict rape, servitude, and other horrors on women).

Posthumanism argues that our desperate urge to salve the wounds of non-meaning through existential ‘therapies’ like faith and reason will never work. Instead, we should embrace our fundamental immanence; experience the fullness of being alive and the creative profusion that is life. It is what it means to be ‘schizoid’, in the Deleuze and Guattarian sense, to fully embrace the excess of life that comes when we let go of our nihilism and resentment, our desperate urge for certainty, reason, and our fantasies of command and control.

This is the nature of immanence. Not deferring life to an ideal that exists ‘outside’ of life (Plato), the endless negation that comes with the pursuit of logic and reason through science and ‘discovery’ (Descartes, Hegel), or the salvation to come from a life beyond this life (religion and many forms of spirituality), but the radical opening to creation that comes when we dispense with intellect and allow for the intuition and the endless repetition of difference to take centre stage.

To summarise all of this very partial summary of a posthuman methodology:

‘It is only by adopting the temporal perspective that we are able to think beyond the perspective of the human being and grasp the nature of reality as such’ (Roffe 2020, p.84).

And now, increasingly, the natural sciences are becoming aware of the need to move away from ‘spatial’ thinking;

’Everything we thought was stable, from subatomic particles to the cosmos at large, has turned out to be in motion. From the acceleration of the universe to the fluctuation of quantum fields, nothing in nature is static. The universe is expanding in every direction at an accelerating rate. What Einstein once thought was an immobile finite universe has turned out to be an increasingly mobile one. This acceleration also means that even space and time are not a priori structures, as we once thought, but continually emerging processes in an unfolding universe.

‘Even at the smallest levels of reality, what we previously thought were solid bodies and inviolable elementary particles, physicists now believe to be emergent features of vibrating quantum fields. These fields’ movement can no longer be understood as ‘motion through space, evolving in time’ as Newton had once understood it. Where an object is and how it is moving can no longer be determined at the same time with certainty. The old paradigm of a static cosmos built from static particles is dead. All of nature is in perpetual flux’ (Nail, 2021, p. 1).

But perhaps the last word should go to Gilles Deleuze, who explains how we might go about posthuman thinking like this;

’This is how it should be done: Lodge yourself on a stratum, experiment with the opportunities it offers, find an advantageous place on it, find potential movements of deterritorialisation, possible lines of flight, experience them, produce flow conjunctions here and there, try out continuums of intensities segment by segment, have a small plot of new land at all times’ (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987, p. 161).

I want to see things as they arewithout me. Why, I don’t know

As a kid I always lookedat roadkill close up, and pokeda stick into it. I want to look at death

with eyes like my own baby eyes,not blinded by knowledge.

I told this to my friend the monkand he said, Want, want, want.Roadkill, by Chase Twichell

Search for posthumanism in the academic health literature and you’re most likely to land on something that comes from the critical posthumanisms.

The absolute necessity of finding new levers to drive a stake into the heart of vampiric capitalism and normative Western hetero-patriarchy has led many to see posthumanism as a way to further feminist, postcolonial, disability, and queer thinking and practice.

There’s a detailed reading list for work in this space at the bottom of the page.

But, for me, there is a problem with much of this literature, and that is that it often fails to escape the humanism that it aspires to critique.

Like someone casting a fishing line out into a flowing stream, the initial promise of escaping anthropocentrism is there, but then the line is always reeled back in returning it to the spool that is humanism.

You will find lots of new methodological adventures, methods, and ideals expressed in critical posthumanism, but the research all too often comes back to the questions that others pose for us.

The argument from critical posthumanists is well known: how can we be otherwise than human? Isn’t the point very point of posthumanism to think differently about our place in the world? Isn’t it meant to make possible a more fluid, diffuse, and minoritarian human; one that recognises both its awesome power to destroy the world but also its absolute cosmic insignificance? And can we ever escape our anthropocentrism anyway? Isn’t a bit of anthropomorphism — as Jane Bennett argues — okay?

And while I have no problem with this argument as a justification for critical research, it can be hard sometimes to see how this work is truly posthuman.

In my mind, the real radical potential of posthumanism is the possibility that humanism can be left behind. Entirely.

Deleuze used the metaphor of the clinamen — a term referring to the smallest angle by which an atom deviates from a line (link) — to make a philosophical point about the nature of posthuman thinking.

He argued that philosophy should trace an escape path from the orbit of normal thought. All too often, though, the gravitational force of critical theory pulls the researcher back into re-entry and ultimately lands their work in an all-too-familiar orbit.

What follows is a brief list of some of the material that I feel comes closest to describing an escape path from the planet ‘People’. But for good measure, I’ve added a second list towards the bottom of the post of some of the key works in critical posthumanism.

It’s a very dynamic field and one that’s growing by the day, so if you think I’m made any gross omissions, please let me know and I’ll update the list.

Five key works of posthumanism (well, six really)

Deleuze’s Difference and Repetition and Logic of Sense

A bit of a cheat straight off the bat to include two books in one, but D&R and LoS are considered by many to be conjoined works. Written during the student riots in Paris in 1968 — a time in which Deleuze spent six months in hospital recovering from a lung resection after years of debilitating TB — they are considered by some to be Deleuze’s greatest works. While Anti-Oedipus and A Thousand Plateaus caught people’s attention, D&R and LoS set everything that followed in place. Truly remarkable texts.

Arjen Kleinherenbrink’s Against Continuity

Kleinherenbrink’s 2019 book argues that everything is a machine. Drawing links between Deleuze’s entire corpus with the field of speculative realism, Kleinherenbrink shows how Deleuze’s work can be understood as a fourfold structure. Radical, highly innovative, and critical response to the shortcomings of affect theory.

Jon Roffe & Hannah Stark’s Deleuze and the Non/Human

A highly recommended collection of writings that explore a lot of the philosophical, theoretical, and methodological issues involved in posthumanism. Like all of Roffe and Starks’s separate works, Deleuze and the Non/Human is beautifully written and curated and would be accessible to most readers. It includes contributions from Elizabeth Grosz, Simone Bignall, Clair Colebrook, Sean Bowden, Ashley Woodward, and others, as well as the editors themselves.

Manuel de Landa & Graham Harman’s Rise of Realism.

A book that takes the form of a long dialogue between the authors and uses their conversation to unpack their different ontological positions and those of their critics and collaborators. Hugely useful for understanding the field of posthumanism and for getting a better grasp on the principles underpinning the work of these two important thinkers.

Richard Grusin’s The Nonhuman Turn

This edited collection includes contributions from Jane Bennett, Brian Massumi, Erin Manning, Timothy Morton, Rebekah Sheldon and others, and like Rolfe and Stark’s book begins from the basis that ‘we have never been human’ (Latour). It’s a great reader on some of the intellectual currents running through contemporary posthumanism, including ANT, assemblage theory, new media theory, and cognitive science.

Notable mentions

Some other highly recommended works that didn’t make the top 5:

Thomas Lemke’s The Government of Things— Foucault as a posthuman

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s Cannibal Metaphysics — the ethics of consuming others

Tristan Garcia’s Form and Object — How objects take form

Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra — Not at all superman

Henri Bergson Matter and Memory - Time, space, past, present, and future all reimagined

Graham Harman’s Immaterialism — Withdrawn objects

Erin Manning’s Relationscapes — Movement happening before it happens

Brian Massumi’s Parables of the Virtual — Technology, sensation, movement and affect

Full list of references

Adam, S., Juergensen, L., & Mallette, C. (2021). Harnessing the power to bridge different worlds: An introduction to posthumanism as a philosophical perspective for the discipline. Nursing Philosophy, 22(3).

Alaimo, S. (2010). Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self. Indiana University Press.

Alaimo, S. (2014). Thinking as the Stuff of the World Link

Badmington, N. (2003) Theorizing posthumanism. Cultural Critique 53(1): 10–27.

Barad, K. (2003) Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs 28(3): 801–831.

Barad, K. (2007) Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke University Press.

Barad, K., Nelson, L. H., & Nelson, J. (1996). Meeting the universe half way: Realism and social constructivism without contradiction. In L. H. Nelson & J. Nelson (Eds.), Feminism, science and the philosophy of science (pp. 161-194). Kluwer.

Bennett, J. (2010) Vibrant Matter. A Political Ecology of Things. Duke University Press.

Bennett, J. (2015). Systems and things: On vital materialism and object-oriented philoosphy. In R. Grusin (Ed.), The Nonhuman Turn (pp. 223-239).

Bignall, S. (2015). Iqbal’s Becoming-Woman in The Rape of Sita. In J. Roffe & H. Stark (Eds.), Deleuze and the Non/Human (pp. 122-141). Palgrave Macmillan.

Bordo, S. (2023). Goodbye, postfeminism Link

Boundas, C. V. (2005). Ontology. In A. Parr (Ed.), The Deleuze Dictionary (pp. 191-192). Columbia University Press.

Bozalek, V., & Zembylas, M. (2016). Critical posthumanism, new materialisms and the affective turn for socially just pedagogies in higher education: part 2. South African Journal of Higher Education, 30(3), 193-200.

Braidotti, R. (2013). The Posthuman. John Wiley & Sons.

Braidotti, R. (2019). A Theoretical Framework for the Critical Posthumanities. Theory, Culture & Society, 36(6), 31-61.

Braidotti, R. (2020). “We” Are In This Together, But We Are Not One and the Same. J Bioeth Inq, 17(4), 465-469.