Process philosophy in healthcare - Part 4

It's about time

The last three posts in this series on process philosophy in healthcare have given a brief introduction to the issues, talked about how process philosophy rejects the idea of objects, matter and things, and tackled the problem of transcendence.

This post is about time and the radical way process philosophy differs from the kinds of substance philosophies that have dominated Western scientific thinking, especially in the health sciences, for centuries.

It’s really not possible to overstate how crucial the question of time is in process philosophy; how fundamentally it challenges our commonplace understandings about things like the past, present, and future; and how important it’s now becoming in helping us understand cosmic (dis)order.

To understand just how radical process philosophies of time are then, we should probably begin with what they oppose.

Health time in the age of Newton

To begin with, we should locate time within contemporary Western healthcare.

Biomedicine, to which most of our practices subscribe, conforms to a Newtonian notion of space and time.

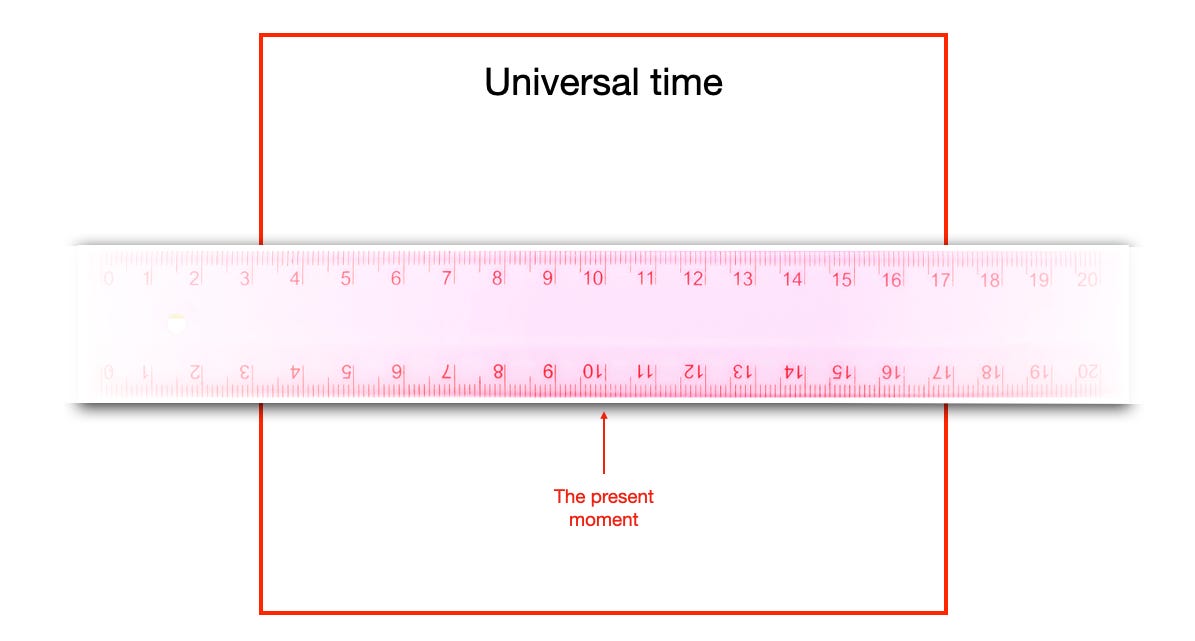

Time, in the Newtonian sense, is a static, fixed, grid-like universal medium upon which events in the present play out.

The ‘upon which’ is the crucial point here. Essentially, there are two kinds of time in a Newtonian world, made up of ‘real moments’ played out against a backdrop of an eternal ideal form of time.

In the classical sense, for there to be a past, present and future, we must be able to differentiate between what is happening to us now from what has happened to us before and what might yet befall us. So, Newton proposed that there needed to be some kind of ‘container’ for time that sits outside our everyday phenomenal experience. In effect there are needed to be two kinds of time: a lived time and a universal referent that different phenomenal experiences of time referred to.

And this idea of time’s arrow has been central to our understanding of how the world works over the last half millennium.

There would be no banking without the concept of debt and interest; little fiction without remembrance of times gone by or future fantasy; little paid labour without the working day; few measurements without seconds, minutes and hours (still the language of nautical navigation); and so on.

Notice though how much the Newtonian idea of time makes reference to time not in its own terms but rather as a spatialised concept.

Space and time

Imagine you are walking down the road in a strange town. You pass shops, cafes, demolition sites and parks, and as you walk something catches your eye; a fleeting image that punctures your mindless ambling and brings you up short.

You stop and retrace your steps and scan the flyers on the shop door for the fleeting image that you were sure meant something. Where is it… Where is it… Ah, there! A poster for a band you once loved, playing in town tonight.

But notice something interesting about this brief vignette: we can easily retrace our steps — go back over the space we trod moments before — but cannot go back in time. Time’s arrow only runs forwards: from the past to the future, pausing only fleetingly to register the present.

‘If I glance over a road marked on the map and follow it up to a certain point, there is nothing to prevent my turning back and trying to find out whether it branches anywhere. But time is not a line along which one can pass again. Certainly, once it has elapsed, we are justified in picturing the successive moments as external to one another and in thus thinking of a line traversing space; but it must then be understood that this line does not symbolize the time which is passing but the time which has passed’ (Bergson, 1910).

So we end up in an difficult situation in which we perceive space and time differently. Because you can travel back in space but not in time, we believe that space and time must be fundamentally different things. And, in a Western sense, time is always subordinated to space.1

We talk about events in time being near to us or in our distant memories; the future is in front of us and our past behind; we say that we will return to the past one day, as if it were a once-loved destination; we talk of being here now; and we say “at this point in time”.

But according to many, this spatialisation of time is fundamentally mistaken.

Physicist N. David Mermin, for instance, reminds us that;

‘Space and time and spacetime are not properties of the world we live in but concepts we have invented to help us organize classical events. Notions like dimension or interval… are properties not of the world we live in but of the abstract geometric constructions we have invented to help us organize events’ (Mermin, 2009).

And in linear, chronological time, ‘the past’ appears no longer to exist. It is gone and is no longer real. Something becomes nothing as the present recedes into the past. All we have in linear time is the notion of an endlessly inaccessible ‘now’ surrounded by nothing.

But what is this ‘now’ that we think of when we think about present time?

Zeno’s paradox

Here is a classic paradox created when we think about time spatially.

If an object is moving along a line from point A to point B, it must first pass through a point half-way between the two.

But to get from where it is now to point B it must then pass through another mid-point, then another, and another in infinitely diminishing fractions.

So, according to Zeno, nothing ever arrives at its destination because the distance it takes to get there is infinitely divisible.

Put another way, if we think of time spatially, each ‘instance’ of time must be a definite static ‘point’. In other words, immobile.

And if each instance of time is fixed and immobile, there can be no motion and, paradoxically, no ‘instant’.

So if our view of space and time is at best a convenient fiction, and at worst completely erroneous, what are the alternatives?

Bergson’s duration

The first person who challenged the classical notion of Newtonian time in the public’s imagination was probably Albert Einstein, who needed to establish a different concept of time in order to explain general relativity.

Einstein showed that there was no universal time, and that the present moment and the passing of time were relative to the observer. In effect, there were many times depending on one’s position in space. ‘Time is relative to systems of reference (different observers), and therefore irreducibly plural’ (Roffe, 2020, p.93).

Henri Bergson came to international prominence by arguing that the young genius physicist was wrong in this regard. Although Bergson thought Einstein had done more than anyone to challenge the classical conception of time, he believed Einstein had really only replaced one spatialised concept of time with another.2

Bergson, by contrast, proposed a notion of time that was far more radical.

Time, Bergson argued, should not be thought of as the continuation of a series of discrete moments — like the 16 frames per second of an old motion picture — but rather as the continuation of change.

Bergson rejected the idea of a single, universal, homogenous, quantitatively measurable concept of time. He rejected the idea of time as an arrow, running from the past through the present and into the future. And he also rejected conventional notions of causality, which relied upon the idea that past events manifested in the present.

Bergson instead argued that there was only one ‘time’ and that it was constantly moving. The past was not a reference to something now gone, but an expression for a virtual state that was as real as the present.

Many possible presents were possible — giving us what we might understand as the ‘future’ — and so the present was not a mirror of the virtual, but merely an actualisation of one possible event among many. The past does not precede the present, but is endlessly folded, unfolded and refolded into it.

And to get away from the spatialised language of time, Bergson used the word duration and spoke of its contraction, relaxation and expansion of time rather than its location before, behind, or in front of us.

Duration for Bergson was multiple, unmeasurable, relational, enfolded, continuously flowing and changing, and its effect on philosophy in the C20 has been profound.

Whitehead’s process philosophy and his concepts of concrescence and actual occasions owe a huge debt to Bergson, as does Heidegger’s work on ‘ungrounding’. But it is probably in Deleuze’s work that Bergson’s duration finds its most important and compelling expression.

The Deleuzian difference

Deleuze more than anyone revived interest in Bergson. Having been internationally famous in the 1920s, Bergson fell out of favour particularly among analytic philosophers in Britain and North America, and he was little studied until the latter part of the C20.

But Deleuzian concepts like the plane of immanence, territorialisation and deterritorialisation, the time image and movement image, and his own construction of the past, present and future in his three syntheses would not have existed without Bergson.

Take Deleuze’s concept of difference, for instance.

Difference is a fundamental idea for Deleuze. But Deleuzian difference is a very particular thing combining the idea of immanence from Spinoza and the idea of duration from Bergson.

Spinoza argued that there was no hard distinction between the physical and mental world. Indeed, he argued that there were no two ontologically separate substances, different in character, anywhere in the cosmos. There was no hierarchy between a superior one and an inferior other: no binary states at all; no transcendence, only the immanence of one substance shared by all things.

This kind of monism created a problem though, because how could we know the difference between one thing or another (God and man, for instance) if everything was the same? And how could new things emerge when all substance was fundamentally the same?

Deleuze answered this problem by showing that it is the way substance expresses itself that makes the difference. Expression here isn’t the product of some deeper-lying substance, but that which produces the attributes that give events, occasions and processes their character.

Expression is temporal, then. But, as I’ve argued, all existing models of time were fundamentally ‘spatial’. So Deleuze turned to the writings of Henri Bergson to explain the temporal quality of expression.

Rather than the production of new static structures from more fundamental matter, Deleuze proposed, following Bergson, that reality was a process of durational folding, unfolding and refolding, arguing that this folding conferred weight, meaning, pressure, and significance on events.

Deleuze finds examples of Bergsonian duration in lots of places: in Lewis Carroll’s writing, in Antonin Artaud’s howls and Francis Bacon’s paintings, in masochism and the schizoid personality, in the ‘streaming, spiralling, zigzagging, snaking, feverish line of variation’ (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987, p.499) found in sorcery and nomadism, in the cinema, and in the ‘baroque movement of endless foldings and unfolding’ of Leibniz (Deleuze, 1993, p.139), and Nietzsche’s eternal return.

So where space is a ‘multiplicity of exteriority, of simultaneity, of juxtaposition, of order, of quantitative differentiation, of difference in degree; it is numerical multiplicity, discontinuous and actual’, duration is ‘an internal multiplicity of succession, of fusion, of organisation, of heterogeneity, of qualitative discrimination, or of difference in kind; it is a virtual and continuous multiplicity that cannot be reduced to numbers’ (Deleuze, 1988, p.38).

What does this mean in practice?

Perhaps without realising it, people may be have been looking for alternative ways of thinking durationally for some time now.

Most health professionals recognise the limitations of quantitative measurement and its reductive focus on time. Quantitative chronological time just can’t account for the the fluidity, ambiguity and plasticity of time that we see all the time in real clinical practice. But phenomenological time also has its problems: its resistance to measurement, its humanism and, from a process perspective, its pursuit of static ‘being’, being not the least of these.

Some have looked to putatively ‘holistic’ models of health like the biopsychosocial model as a way to break with the Western view of time, but these have only shown so far a very limited ability to depart from the fundamental tenets of rational Western scientific thought.

Some have turned to indigenous cosmologies and ancient forms of wisdom like Buddhism and Hinduism for alternative approaches to time, but many indigenous cosmologies are fundamentally transcendent (relying deeply on spiritual domains ‘beyond’ this world), and many ancient wisdom traditions work better as modes of living than as explanations for the fundamental nature of reality.

Of course, we should remember that the primary reasons for holding on to a classical notion of clock time are tied to the West’s pursuit of unlimited growth and capitalistic efficiency, the management of time and labour, and the Protestant tradition tying work to salvation and human flourishing. (Think here of the importance for commerce of standardising Greenwich Mean Time.) So the arguments for a different way of thinking about time as duration will not take root simply because they are more ontologically accurate.

Perhaps this is why an enormous amount of attention has been directed towards quantum physics in recent years.

Quantum physics and quantum mechanics attempt to overturn centuries of Newtonian mechanistic thinking in science.

Tellingly, they have a huge amount of resonance with Bergsonian and Deleuzian philosophies of flux and flow, movement and duration. Physics and philosophy singing the same tune, you might say.

Quantum physics argues that time and space are constructed in the present and are not pre-existing states to which the present ‘refers’. Quantum physics provides empirical evidence for concepts like superposition (as a way to explain consciousness, for instance), wave-particle duality, uncertainty, entanglement, and the existence of many simultaneous instances of time3 — all concepts that defy conventional scientific wisdom and conform much more closely to process philosophies.4

Perhaps, then, we need to start thinking about health and illness in durational terms?

How would concepts like pain, disease, depression, healing, and therapy change if we looked at them as temporal/durational events rather than spatially-bound ‘things’?

How might our assessments, tests and treatments alter if our goal was durational flow rather than definitional clarity and stasis?

How might we reimagine cause and effect when the past isn’t something lying behind us in psychological memory but is folded into the present?

In the next post I’ll try to tackle a question at the heart of new thinking about duration, and one of real significance in healthcare, and that is the subject of movement, and how this too might also now by up for revision.

References

Angulo, D., Thompson, K., Nixon, V., Jiao, A., Wiseman, H. M., & Steinberg, A. M. (2024, September 5). Experimental evidence that a photon can spend a negative amount of time in an atom cloud. arXiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.03680

Bergson, H. (1910). Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness (F. L. Pogson, Trans.). F.L. Pogson. Swan Sonnenschein.

Deleuze, G. (1988). Bergsonism. Zone Books.

Deleuze, G. (1993). Difference and repetition. Columbia University Press.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus — Capitalism and schizophrenia (B. Massumi, Trans.). University of Minnesota Press.

Hossenfelder, S. (2022). Existential Physics: A Scientist’s Guide to Life’s Biggest Questions. Atlantic Books.

Kemper, J. (2024). Deep Time and Microtime: Anthropocene Temporalities and Silicon Valley’s Longtermist Scope. Theory, Culture & Society, 41(6), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/02632764241240662

Mermin, N. David. “What’s Bad about This Habit”, Physics Today 62 (2009), pp.8-9. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3141952

Neven, H., Zalcman, A., Read, P., Kosik, K. S., van der Molen, T., Bouwmeester, D., Bodnia, E., Turin, L., & Koch, C. (2024). Testing the Conjecture That Quantum Processes Create Conscious Experience. Entropy (Basel), 26(6), 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/e26060460

Orf, D. (2024, August 13). Quantum entanglement in your brain is what generates consciousness, Radical study suggests. Popular Mechanics. https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/a61854962/quantum-entanglement-consciousness/

Padavic-Callaghan, K. (2024, September 5). Can we solve quantum theory’s biggest problem by redefining reality? New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg26335070-700-can-we-solve-quantum-theorys-biggest-problem-by-redefining-reality/

Roffe, J. (2020). The works of Gilles Deleuze: Volume 1 - 1953-1969. re.press. https://re-press.org/

Rovelli, C. (2021). Helgoland: Making Sense of the Quantum Revolution. Penguin.

Wagh, M. (2024, September 26). Your consciousness can connect with the whole universe, groundbreaking new research suggests. Popular Mechanics. https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/a62373322/quantum-theory-of-consciousness/

Wood, C. (2024, September 25). The Thought Experiments That Fray the Fabric of Space-Time | Quanta Magazine. Quanta Magazine. https://www.quantamagazine.org/the-thought-experiments-that-fray-the-fabric-of-space-time-20240925/

Tennessee Williams once described time as ‘the longest distance between two places’.

There are even studies in quantum physics showing evidence that time can flow backwards.

For more on the possibilities of quantum physics, see, Rovelli, 2021; Angulo et al, 2024; Hossenfelder, 2022; Kemper, 2024; Neven et al, 2024; Orf, 2024; Padavic-Callaghan, 2024; Wagh, 2024; Wood, 2024.