Sense and nonsense

After a brief detour into practice last week, I’m returning today to the complicated concept of ‘the virtual’ in process philosophy.

In the first post in the series, I tried to explain all of the things the virtual wasn’t. For instance, you can’t think of the virtual as a transcendental realm ‘beyond’ this world, nor as a metaphor or model of the unconscious. It’s not some kind of ‘warehouse’ where real things are stored, nor is it pure potential.

It is however ubiquitous, real, more than meets the eye, and profoundly common.

The virtual is also non-spatial. It has no ‘extension’, meaning it takes no shape or form. It is temporal, or, more accurately, durational, and makes us completely rethink the ideas of the past, present and future; an aspect I explored in more depth in the second post in the series.

Now, in this post I want to tackle the relationship between the virtual and the concept of sense.

One of the most beguiling features of process philosophy is how every concept seems to run into every other. Like a tie-dyed shirt; one colour bleeds into everything else.

But of course, process philosophy has to do this, because it is the antithesis of a substance philosophy that works so hard to create clear boundaries between things. Process philosophy wants everything to be interstitial. And so it is with the ideas of sense, nonsense and the virtual.

When we use the word sense it can mean a number of things. It can denote, manifest and signify something. But we always think of it as a sort of ground to the meaning we give to things. And in humans, sense is most often conveyed through language, although non-verbal communication can convey sense, too.

A century ago though, linguists like Ferdinand de Saussure showed that sense was conveyed as much by what things were not — their negative space, if you will — as what they seemingly were. Derrida’s later work on deconstruction developed this idea further.

What these early post-structuralists showed is that there is always something that escapes the ground of sense; something that exceeds literal translation.

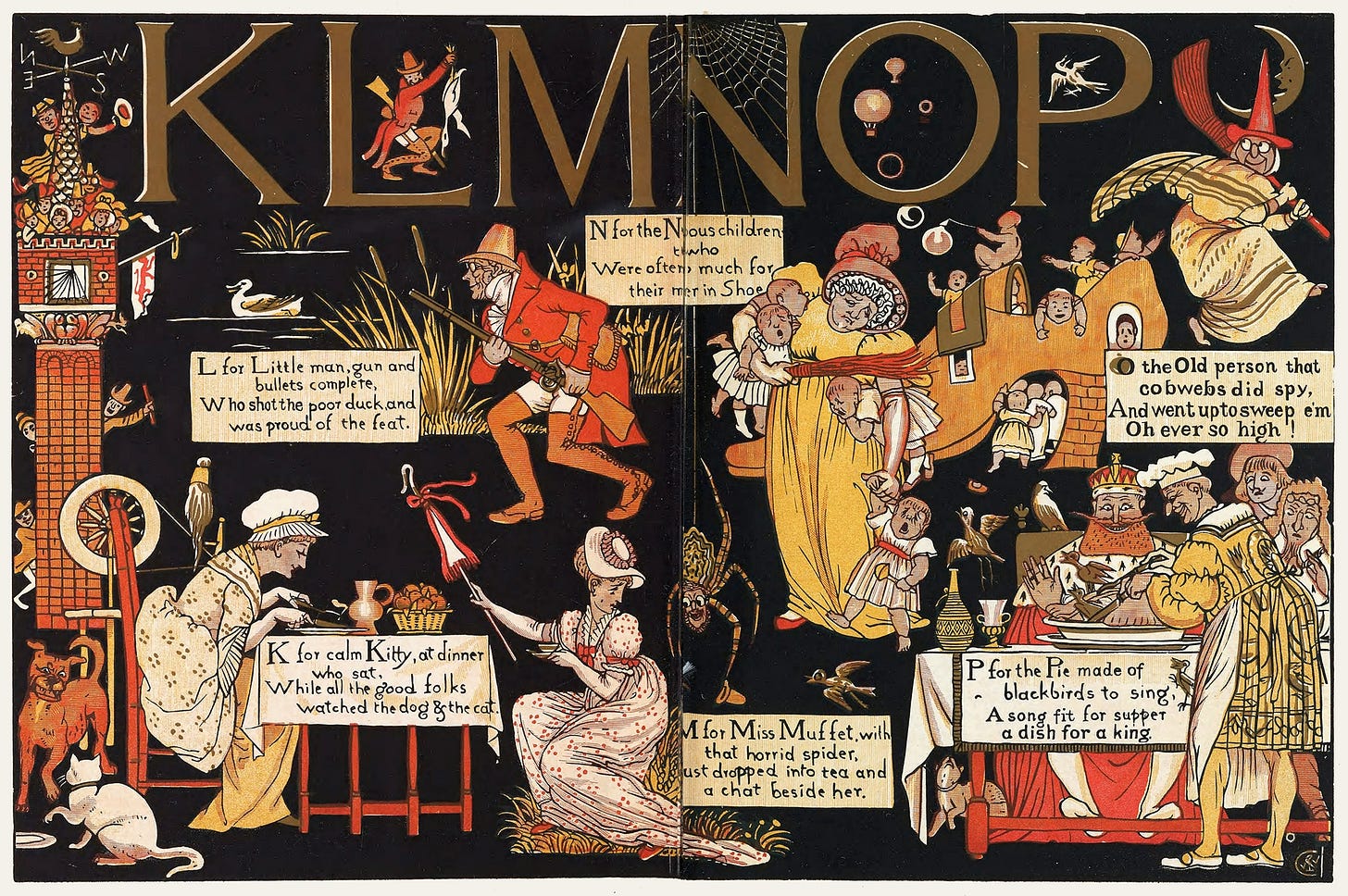

Writers like Lewis Carroll — much beloved of Deleuze — make heavy use of this ‘inexpressible outside’ of language, inventing portmanteau words that seem somehow to convey meaning without having any anchor in sense. Words like slithy (from lithe and slimy), chortle (chuckle and snort), and mimsy (miserable and flimsy) force us to go beneath literal meaning-making and search for the nonsense in sense.1

In Logic of Sense (Deleuze 1969), Deleuze was interested to see what led sense to its limit; what stripped language of its inherited meaning, and allowed a glimpse into nothing but sense.

Deleuze was interested to find the flip side of sense; the untethered, non-spatial movement that has no form, no extension, and yet makes sense possible.

We know that such a form of nonsense exists because there is always something inexpressible that exceeds sense. But crucially, what Deleuze argued was that we don’t derive nonsense from sense — we don’t produce non-meaning in the act of ascribing meaning to things — rather, nonsense precedes sense. Nonsense is the engine, the machine that makes all thought possible.

Now, this bears repeating, but I’m not talking about thought in the psychological sense here, but rather a form of thought — or ‘feeling’ as Whitehead preferred — that is common to all occasions, events and things throughout the cosmos. So, cushions, hopes and dreams and forest fires all ‘think’ ontologically in the same way as we do (although the way we think is unique to us).

So, for Deleuze, nonsense is not some kind of ghostly residue of sense-making, it is radically full. Nonsense is the entire universe of possible meaning from which sense derives. Nonsense is the real, virtual world from which bodies and qualities are formed.

Here we see a tie-back to the last post and the idea of ‘the past’ in process philosophy. The past is not a place where memories go, but rather a flow that exists like one of two jets flying alongside the present. Where the future remains always radically empty, the past (nonsense) is completely stuffed with life, from which the present (sense) draws.

Nonsense is the Body-without-Organs, deterritorialisation, smooth space, the plane of consistency, and what Bergson called intuition.

Crucially, whenever nonsense produces sense, it bequeaths not only the possibility of life to sense, but also the absolute possibility of death. Death haunts every act of creation, and the risk that sense is still-born at the moment of its creation underpins the idea of difference and creative evolution.

Deleuze argues that nonsense is the genetic centre and quasi-cause of sense. This is an odd term, but what Deleuze means to show is that nonsense and the virtual are always inaccessible to the parts of an entity that enter into relations with other things. The ground of sense can never fully access ungrounded nonsense, although everything ‘has a shot’ (Kleinherenbrink 2018).

Reference

Deleuze, G. (1969). The Logic of Sense. Columbia University Press.

Kleinherenbrink, A. (2018). Against Continuity: Gilles Deleuze’s Speculative Realism. Edinburgh University Press.

A number of other authors used language techniques like this in their writing, and they provide some great methodological pointers for anyone wanting to break out of more traditional forms of thinking and practice. James Joyce initially coined the word quark, for instance, which was then taken up by physicists, and Edward Lear wrote about ‘runcible’ spoons in The owl and the pussy-cat. No-one yet knows what a runcible spoon is. But that hardly seems to matter.

Really enjoying these posts. Who (or what) makes sense? And how can sense be made in a present that is “radically empty”?

Hi Louis.

For Deleuze there's an odd relationship between sense and nonsense, past and present, virtual and real, grounding and ungrounding (they're broadly treated as synonymous). They are 'folded' into each other, but also radically separated.

So we don't 'discover' sense in the manner you're talking about, because that might imply that sense was there all along waiting for us to find it. (If that were the case we'd have to ask who or what created this originary sense, and that introduces a transcendental 'other' again that Deleuze is so keen to avoid.)

So, sense isn't discovered; it's created from nonsense, and nonsense is created from sense, in a constant in and out, back and forth.

This is why the past and memory are such radically different things for D&G and Bergson, because they're not a storehouse or bank account that we build over time and draw on when we need to (in a temporal 'past'); they're 'immanent' being fully in the present. They're just virtual, and we actualise them by thinking and speaking about them.

Hope that helps.

Dave