When I think about it, I’ve been interested in the idea of minimalism for a long time. Minimalism is the idea of stripping things back to their most basic essence.

Although I’m not a phenomenologist, Edmund Husserl’s phenomenological method is a good illustration of an attempt to get to the essence of the thing.

Husserl thought by bracketing (consciously setting aside) our positionality, we might be able to slough off the layers of sludge that over time build up around the things we engage with in the world.

In theory, it makes no difference whether you want to know what a socket wrench really is, or want to get to the true nature of capitalism; the method is the same.

I tried to make a Husserlian case of sorts in the final chapter of Physiotherapy Otherwise, when I suggested that we needed to slough off the adumbrations (Husserl’s word for ‘shadows’) that had been built up around the physical therapies over the years.

There is something true, beautiful, and precious at the heart of the physical therapies, and my argument was that we had lost this in the search for social capital and professional prestige.

A more minimalistic approach might win it back.

There is no shortage of references to minimalism in the arts, but few direct references in healthcare.

In music, for instance, you have artists like Basic Channel (Moritz von Oswald and Mark Ernestus) whose experiments in electronic music in the 1990s have been so influential.

Oswald and Ernestus tried to strip music back to pure rhythm. What would music sound like, feel like, if it was stripped of all of the singing, lyrics, narrative flow, melody and tune? What they engineered was something quite remarkable.

I’ve listened to a lot of beautiful music over the last 50 or so years, but this would be without doubt one of my all-time favourite pieces of music.

Nearly 14 minutes of rhythmic, pulsing repetition in which nothing happens, repeatedly.1

I could honestly listen to this all day. There are no annoying cliched lyrics to distract you, no singer trying to impress you with their vocal range or emotional depth. It’s just gently tesseral throbbing. To my mind, it’s what nature would sound like if I were a bee or a plant. Constant, repetitive, warm, and comforting.

The poet Kenneth Goldsmith does a nice line in minimalism.

Here’s a description of his work from a 2011 interview with Dave Mandl;

‘In books like No. 111 2.7.93–10.20.96, a massive compendium of words and phrases ending with the r sound, alphabetized and sorted by length; Soliloquy, which documents every word he uttered in a week; The Weather, a transcript of an entire year’s worth of weather reports on news station WINS; and Day, for which he retyped the entire contents of an issue of the New York Times, Goldsmith has produced monumentally “boring” texts that shun all frills and artfulness’ (Mandl, 2011).

In the interview Goldsmith said this;

“The moment we shake our addiction to narrative and give up our strong-headed intent that language must say something “meaningful,” we open ourselves up to different types of linguistic experience, which, as you say, could include sorting and structuring words in unconventional ways: by constraint, by sound, by the way words look, and so forth, rather than always feeling the need to coerce them toward meaning. After all, you can’t show me a sentence, word, or phoneme that is meaningless; by its nature, language is packed with meaning and emotion. The world is transformed: suddenly, the newspaper is détourned into a novel; the stock tables become list poems” (ibid).

I like that.

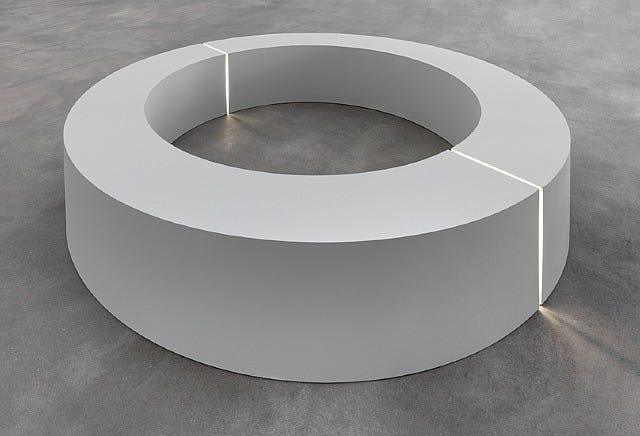

Then there are visual artists like Donald Judd, Anne Truitt, Carl Andre, Dan Flavin and Agnes Martin.2

Their works might not be to everyone’s taste, I understand, but they are trying to achieve something important.

They’re trying to make the materials they use speak for themselves; stripped of the sludge of existential meaning. They’re trying to make sense of materials and the spaces they take up in the world without words; or maybe exploring a deeper sensual language in the simplest unmediated way.

It’s a kind of spiritual minimalism; a Taoist or Zen-like search for simplicity, quiet, stillness.

So what of therapeutic minimalism?

Although it never features in the healthcare literature, it seems to me the idea of therapeutic minimalism has some resonance.

Maybe there is already some minimalism at work in the way we search for the specific aetiology (cause) of an illness when we’re doing diagnostic work?

Maybe the bracketing of our subjectivity and attempt to look beyond the presenting signs and symptoms is itself a kind of minimalism?

And when we ‘prescribe’ (do we still use that word?) exercises, drugs, or other treatments for people, are we attempting to strip away all of the contextual clutter of people’s lives so that these three sets of 10 can take their effect?

There’s a lot of minimalism in the repetitive, mundane, de-personalised aspects of healthcare. But there’s also a strong tendency to resist this and make therapy heroic, memorable, meaningful.

Often we only get to see our patients for a few minutes, so of course we want to have an impact.

But I wonder if this isn’t the same impulse that Satie, Basic Channel, Goldsmith, Judd and others are not reacting to?

Does the desire to be heroic, impactful and meaningful as therapists speak more about our own desires and needs than the patient’s?

Does it conceal more than it reveals about the innate beauty of therapy?

If we stripped this ego away — took the personal out of the therapy — could that take us back to the essence of the thing itself?

If that’s the case, couldn’t there be an argument made for a different kind of therapy; one that draws from the arts, perhaps, to explore a quieter kind of care?

References

Mandl, D. (2011). An interview with Kenneth Goldsmith. https://www.thebeliever.net/an-interview-with-kenneth-goldsmith/

Vivian Mercier wrote in the Irish Times in 1956 that Samuel Beckett had written a play (Waiting for Godot) ‘in which nothing happens, twice’.

I’m grateful to my good friend Shirley Chubb for suggesting these artists.

I love this idea of therapeutic minimalism. Remembering it is not about us as amazing physios, it’s about what what the patient needs. I recently had two participants on a clinical trial for people with knee osteoarthritis. They were both very busy and already exercising to a high level at different gyms- even with their chronic knee pain. However, they were largely compensating for quads weakness by doing closed chain type of exercise. My only contribution was to teach them an isometric isolated quads contraction, and convince them to do it regularly to fatigue. Helped them both - to their surprise. Not a theraband or weights machine in sight. The isometric quads contraction - a thing of beauty!!!

Pensé en el poder pastoral de Foucault, en la ignorancia arrogante de Boaventura de Sousa Santos y la falta de resonancia de Harmut Rosa.