Between October and December 2024 I wrote six ‘Stackposts exploring process philosophy. This followed a similar format to ones I’d written on posthumanism and post-professionalism. As with those editions, I’ve collated all six articles here into one compendium for ease of reading.

I’ve removed all of the decorative images and assimilated the references into one long list at the foot of the article.

To cite: Nicholls. D.A. (2024). Process philosophy compendium. ParaDoxa. https://doi.org/10.14426/111224

Part 1 - Introduction

Try this quick experiment: stop what you’re doing. Just for a moment sit or stand completely still. Don’t move, twitch or blink. Stop breathing. Stop digesting, pulsing and synapsing, too. Stop thinking. Suspend ageing. Don’t decay or replenish anything. Don’t change. Stay just as you were a minute ago when this experiment began.

Of course, we all know this isn’t possible. We can never be truly still. Because even when we think we are being still, we are still|moving.

And yet, almost all of the structures that shape our life in the West are governed by this photograph-like framing of reality. We live in a universe of names and identities; things, objects and matter; fixed processes, systems and structures; conventions that can be learned and passed along. The world is a kind of ‘container’ — as George Lakoff and Mark Johnson described it (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980) — full of objects that continually bump into one another making things happen.

We have ordered the world in this way in part because it makes thinking and communicating easier. (Try describing anything to someone else without using nouns, for instance.) It’s also easier to measure something when it has clearly defined properties. And if you can measure something, you can isolate it from everything it is not: measure its relative distance — both figurative and spatial — and give it a discrete, bounded, finite identity. You can group like things together, assign differences, and rank them in order. And, in time, when you have enough of these things, you can engineer a Great Chain of Being.

But is this a true reflection of reality, or merely a convenient projection: an abstraction; an artificial construct superimposed on the world by human minds and human sense(s)? Is this really how the cosmos rocks?

In recent years, a host of theorists and philosophers have critiqued the kinds of substance philosophies that have underpinned Western modes of thinking since the Renaissance. We’ve seen critiques emerge from existentialism and post-structural linguistics, from Marxism and critical theory, and in recent years we’ve seen it in the rise of post-qualitative research and the new materialisms. And most of these owe some allegiance to process philosophy.

Process philosophy is the most widely known alternative to substance philosophy and it extends back to the writings of pre-Socratic philosophers in 6th century BCE. It can also be found in the ancient Eastern traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism as well as being the metaphysical basis of many indigenous cosmologies.

Perhaps the most widely known process philosophers today are Gilles Deleuze, Henri Bergson and Alfred North Whitehead. But there is process philosophy in the writings of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Baruch Spinoza, Karen Barad, Jane Bennett, Mark Bickhard, and Manuel De Landa, John Dupré, Antony Galton, Graham Harman, Charles Hartshorne, Erin Manning, and Quentin Meillassoux, Timothy Morton, Nicholas Rescher, Johannes Seibt and Helen Steward.

All of these are fundamentally process philosophers whose work tries to think through the implications of Heraclitus’s famous process dictum that you can never step in the same river twice.

So, if it is that you can never repeat a breath, feel anything the same way twice, think anything again, or, indeed, stop anything, even for a moment, what does it mean for the way we have systematised and ordered the furniture of our universe thus far? If everything is a process and everything flows, how can we live like that?

But even asking this question suggests an error, because process philosophy tells us that we already are living like that. Life doesn’t stop because we’ve suddenly noticed that we’re in constant motion. The earth won’t stop spinning because we’re suddenly thinking about it. No, the problem is not how to live ‘in process’ — we already are — the problem is how we can know the world in process. How can we understand, use, and make good in a world which rejects the reality of objects, things, identities, being, reduction, and finitude?

Over the course of the next few weeks I’m going to dig into process philosophy a little and explore what it is, how it’s being used, how we might do it well, and how it might be being misapplied. I want to see if I can tease out some of its implications for the way we think about health and healthcare, and how it might offers us some radical new ways to research and practice.

If this is something you yourself have dug into, have some knowledge of, or some materials you’re happy to share, please add them in the comments below. As always, it’s lovely to hear from you.

Part 2 - There are no things in process philosophy

There’s been a lot of interest in process philosophy concepts and ideas in recent years, especially in the more avant-garde qualitative health literature. Terms like assemblage, bricolage, indeterminacy, interstitial space, lines of flight, movement, nomadism, and rhizomes are becoming increasingly popular.

I suspect some of the people using these terms don’t realise these derive from process philosophy. I also suspect that some of these terms are being misused; coopting the new funky language of flux and flow where the work itself is anything but.

But I also think it’s actually really hard to work with process philosophy or, at least, to abandon the substance philosophy we’ve been socialised to for generations.

If you’ve been raised to practice, think and research in the classical Western tradition of reductive, humanistic, instrumental science — as almost all of us have — turning your back on it and adopting an entirely new philosophy is incredibly hard; even if the evidence for process philosophy is all around us all of the time.

So the biggest challenge to anyone wanting to use process philosophy is to fully embrace it and not just use process-lite language to mask an otherwise substance-based metaphysics.

What then are the traps that substance metaphysics lays for us, and how might we know if we’ve truly avoided them?

Let’s begin with the biggest: the pull to give the thing a name.

We think in terms of things

The first, and most obvious, substance-based Heffalump trap we have to face is whether we talk about things, objects, matter, stuff, the furniture of the world, identities, labels, signs or taxonomic references when we should be talking about processes.

Throughout almost the entire history of Western philosophy, and especially since the Renaissance, the concept of substances has dominated thought.

And yet the closest process philosophy gets to the existence of any fixed or stable ‘thing’ is to use terms like metastable states (Nail 2024), temporary concrescences, or actual occasions (Whitehead 1929/1978).

There really are no things in process philosophy.

Now, imagine what this means for how you normally think about health and healthcare.

Try this short exercise: describe your specialist area of work without referring to any fixed, stable, named thing: individual or collective, real or imagined. Hard, isn’t it.

It’s hard because in the Western metaphysical tradition, you and not you are fundamental philosophical absolutes. God made man, didn’t He (sic)? He didn’t make an ongoing process of material flows that manifested temporarily in metastable states that embodied a form we might call Adam and Eve.

So, it’s a cornerstone of substance thinking that we can distinguish ourselves from others.

This idea manifests in so many ways: especially in references to ourselves as autonomous and independent entities, and in our labelling of things and conferring ‘identities’ on all of the stuff around us — actual and virtual, real and imagined, material and immaterial.

Of course, the surrealists were mocking this kind of fixation on immovable, fixed, static things more than a century ago. But such substance-based thinking holds hard in healthcare.

This is not a pipe, it’s a painting of a pipe.

And this isn’t a right sided pneumothorax, it’s a two-dimensional representation of tissue density.

If you were seriously trying to use process philosophy, then, you would have to remember that nothing is ever fixed or stable long enough to bear anything that might serve as a defined identity.

Even when people talk about assemblages and use hyphens to connect different things (the midwife-mother-pregnancy assemblage, for instance), you are still defining three fixed identities and so being pulled back into the Western world of substance thinking.

There is no ‘being’ in process philosophy, only becoming.

An example and some prompts

Here’s the abstract from a paper from 2019 to illustrate the problems of applying process philosophy. There are some questions below that this abstract made me ponder.

‘This paper plateau describes children's interspecies relation with a classroom canine, utilising posthumanism, post-structuralism and new materialism as its research paradigm and methodology. Once feelings are cognitised or articulated, their true essence can be lost. Therefore, elucidating moment-to-moment child-dog interactions through the lens of affect theory attempts to materialise the invisible, embodied, 'unthought' and non-conscious experience. Through consideration of Deleuzian concepts such as the 'rhizome' and 'Body-without-Organs' being enacted it illuminates new, 'situated knowledge'. This is explicated and revealed using visual methods with 'data' produced by both, the children and their classroom dog such as photographs and video footage mounted on the dogs harness, from a GoPro micro camera. In addition, individual drawings, artefacts and paintings completed by the children are profound points in the research process, which are referred to as 'plateaus'. These then become emergent as a children's comic book where their relationship with 'Dave', their classroom dog is materialised. Through their interspecies relationship both child and dog exercise agency, co-constitute and transform one another and occupy a space of shared relations and multiple subjectivities. The affectual capacities of both child and dog also co-create an affective atmosphere and emotional spaces. Through ethnographic, participant observation and the 'researcher's body' as a tool, they visually create illustrations through the sketching of 'etudes' (drawing exercises) to draw forth this embodied experience to reveal multiple lines and entanglements, mapping a landscape of interconnections and relations’ (Carlyle 2019).

Questions and prompts for thoughts:

If the body-without-organs can be read as a body that is not organised into a fixed form, how strongly did you feel the author relied on the fixed identities and normalised social distinctions between the children and the dog to make their case? (I note the dog was called Dave. Apart from this being a clear ‘tell’ of substance-based metaphysics coming through, I’d like to point out that this had nothing to do with me critiquing this paper.)

What did this study add that other existing philosophies and methodologies could not have achieved through arts-based critical theory or post-phenomenology, for example? In other words, what made the ‘process’ difference here?

Did the researcher need to retain their stable identity to do the research? Their use of participant observer and ethnographic methods suggests they did.

Thinking not in terms of things, objects or matter but in terms of true processes seems like it would be a major shift in the way we do quantitative and qualitative research. But we’re only just getting started!

In the next post I’ll move on to another of the substance-based Heffalump traps and talk about the thorny subject of transcendence.

Part 3 - Not of this world

In the last post on process philosophy (link) I suggested that there were no ‘things’: no objects, no stable matter, no essential essences, and no temporally or spatially fixed identities in process philosophy.

In some ways this seems counterintuitive because how can there not be things like people, rocks, clouds, dreams, men and capitalism?

And this is a reasonable question, because don’t we live everyday in a world of things?

Well yes… if our starting point is already biased towards a thing-based mindset.

But if you approach the question of reality as a process thinker, things seem much more straightforward.

We all know the boundary between what’s me and not me is shifting all the time: bodies are in a constant state of interaction with the environment; cells are sloughing off; air and food comes in and out; I cast my mind back to an earlier time; and we are never still. Not a single atom in our make up ever stands still in space or time. Everything flows.

And that’s all process thinking.

So, on the one hand we all know that life is constantly a process, in motion. So why do we always seem to want to stop the clocks, hold the thing still and give it a name?

The answer for this may lie in our age-old desire for transcendence.

Transcendence is a belief in something ‘outside’; something ‘beyond’.

In its most benign sense transcendence just means there is something that is indivisibly ‘me’, and equally something that is ‘not me’. This idea of sovereign autonomy can easily be extended to all things, producing all sorts of binary states:

tree|not tree

male|female

mind|body

subject|object

true|false

nature|culture

order|chaos

right|wrong

human|non-human

sacred|profane

normal|abnormal

alive|dead

good|evil

visible|invisible

healthy|sick

agency|structure

inside|outside

still|moving

mad|sane

public|private

active|passive

self|other

space|time

The first answer to why we might impose a transcendental view on reality, then, is that it just makes life easier. It’s much simpler buying an apple at the supermarket than searching for some vitamin C in an immaterial assemblage of intersecting relations.

But knowing what we agree to call something is not the primary reason we defer to transcendentalism. The primary reason is that transcendentalism gives us a convenient why.

When we invent the idea of an indivisible self or entity — and, by extension, something that is not-me — we are creating the conditions in which we can give the ‘not me’ causal and explanatory power. We can explain events in our life and all kinds of happenings and even the existence of everything in the cosmos in deference to the other; the not-me that makes things real.

God(s), faiths, beliefs in Gaia, nature and mother earth, fate, chance or luck, natural scientific laws, and superstructural powers like capitalism, religion and language are all ‘not-mes’ that we have gifted with super-natural powers in an attempt to make sense of this messy, inexplicable existence.

“Comfort’s in heaven; and we are on the earth” - Shakespeare, King Richard III

But this is not new. For much of human history, from Parmenides and Aristotle to modern-day philosophers and scholars, faith leaders and scientists, we have used the idea of a transcendental realm as a way to explain present realities.

Plato suggested that everything in existence was an imperfect copy of a perfect ‘form’ that lay beyond this world.

Many faiths used the idea of the non-earthly realm as a way to explain creation and fate, maintain connections with gods and ancestors, give a reason for human existence, and — as was the case with the Early Christian church — construct a great chain of being that set ‘man’ apart from nature (Goldhill, 2024).

Scientists from the Renaissance onwards have done this too, by arguing that laws of nature exist ‘out there’, and that our job as rational human beings should be to uncover these laws governing everything within the cosmos.

Kantian idealism threw a spoiler into rational science by arguing that we can never actually know the reality of a thing in itself (noumena) because the world can only be accessed through our senses, so all experience is phenomenal.

Postmodernist theorists like Derrida and Foucault offered the first substantial critique of transcendentalism, arguing that there could be nothing outside of the text or beyond discourse.

In recent years, though, new materialist authors like Jane Bennett have found they cannot escape transcendental vitalism, and that there must be some ‘power’ (what Hans Driesch called entelechy and Henri Bergson’s élan vital) enchanting the world not only of humans but of all things.

Indeed, its an ongoing debate even whether process philosophers like Deleuze and Guattari, Alfred North Whitehead, and speculative realists like Graham Harman fully escape transcendentalism themselves.1

The rejection of transcendentalism remains, however, a cardinal principle of process philosophy which, instead, pursues the idea of immanence. I’ll talk more about this concept in an upcoming post, but our next topic has to be the second crucial error of substance philosophy — in the minds of process philosophers, at least — and that is its entirely abstract and thoroughly misleading construction of time and space.

But more on that next time.

Part 4 - It’s about time

The last three posts in this series on process philosophy in healthcare have given a brief introduction to the issues, talked about how process philosophy rejects the idea of objects, matter and things, and tackled the problem of transcendence.

This post is about time and the radical way process philosophy differs from the kinds of substance philosophies that have dominated Western scientific thinking, especially in the health sciences, for centuries.

It’s really not possible to overstate how crucial the question of time is in process philosophy; how fundamentally it challenges our commonplace understandings about things like the past, present, and future; and how important it’s now becoming in helping us understand cosmic (dis)order.

To understand just how radical process philosophies of time are then, we should probably begin with what they oppose.

Health time in the age of Newton

To begin with, we should locate time within contemporary Western healthcare.

Biomedicine, to which most of our practices subscribe, conforms to a Newtonian notion of space and time.

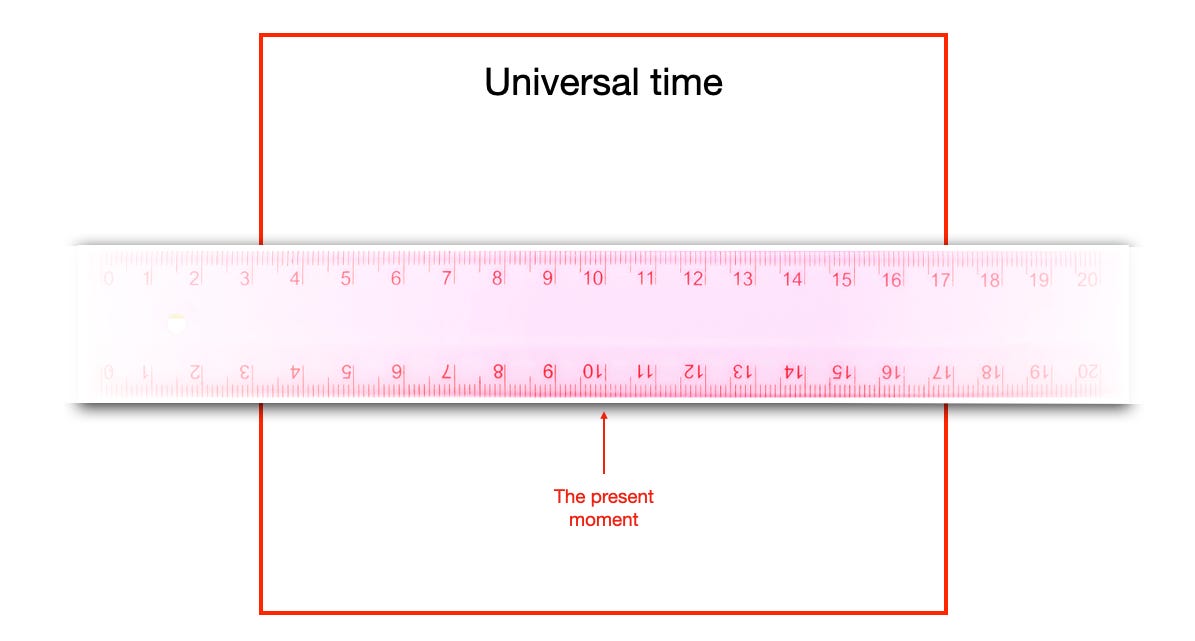

Time, in the Newtonian sense, is a static, fixed, grid-like universal medium upon which events in the present play out.

The ‘upon which’ is the crucial point here. Essentially, there are two kinds of time in a Newtonian world, made up of ‘real moments’ played out against a backdrop of an eternal ideal form of time.

In the classical sense, for there to be a past, present and future, we must be able to differentiate between what is happening to us now from what has happened to us before and what might yet befall us. So, Newton proposed that there needed to be some kind of ‘container’ for time that sits outside our everyday phenomenal experience. In effect there are needed to be two kinds of time: a lived time and a universal referent that different phenomenal experiences of time referred to.

And this idea of time’s arrow has been central to our understanding of how the world works over the last half millennium.

There would be no banking without the concept of debt and interest; little fiction without remembrance of times gone by or future fantasy; little paid labour without the working day; few measurements without seconds, minutes and hours (still the language of nautical navigation); and so on.

Notice though how much the Newtonian idea of time makes reference to time not in its own terms but rather as a spatialised concept.

Space and time

Imagine you are walking down the road in a strange town. You pass shops, cafes, demolition sites and parks, and as you walk something catches your eye; a fleeting image that punctures your mindless ambling and brings you up short.

You stop and retrace your steps and scan the flyers on the shop door for the fleeting image that you were sure meant something. Where is it… Where is it… Ah, there! A poster for a band you once loved, playing in town tonight.

But notice something interesting about this brief vignette: we can easily retrace our steps — go back over the space we trod moments before — but cannot go back in time. Time’s arrow only runs forwards: from the past to the future, pausing only fleetingly to register the present.

‘If I glance over a road marked on the map and follow it up to a certain point, there is nothing to prevent my turning back and trying to find out whether it branches anywhere. But time is not a line along which one can pass again. Certainly, once it has elapsed, we are justified in picturing the successive moments as external to one another and in thus thinking of a line traversing space; but it must then be understood that this line does not symbolize the time which is passing but the time which has passed’ (Bergson, 1910).

So we end up in an difficult situation in which we perceive space and time differently. Because you can travel back in space but not in time, we believe that space and time must be fundamentally different things. And, in a Western sense, time is always subordinated to space.2

We talk about events in time being near to us or in our distant memories; the future is in front of us and our past behind; we say that we will return to the past one day, as if it were a once-loved destination; we talk of being here now; and we say “at this point in time”.

But according to many, this spatialisation of time is fundamentally mistaken.

Physicist N. David Mermin, for instance, reminds us that;

‘Space and time and spacetime are not properties of the world we live in but concepts we have invented to help us organize classical events. Notions like dimension or interval… are properties not of the world we live in but of the abstract geometric constructions we have invented to help us organize events’ (Mermin, 2009).

And in linear, chronological time, ‘the past’ appears no longer to exist. It is gone and is no longer real. Something becomes nothing as the present recedes into the past. All we have in linear time is the notion of an endlessly inaccessible ‘now’ surrounded by nothing.

But what is this ‘now’ that we think of when we think about present time?

Zeno’s paradox

Here is a classic paradox created when we think about time spatially.

If an object is moving along a line from point A to point B, it must first pass through a point half-way between the two.

But to get from where it is now to point B it must then pass through another mid-point, then another, and another in infinitely diminishing fractions.

So, according to Zeno, nothing ever arrives at its destination because the distance it takes to get there is infinitely divisible.

Put another way, if we think of time spatially, each ‘instance’ of time must be a definite static ‘point’. In other words, immobile.

And if each instance of time is fixed and immobile, there can be no motion and, paradoxically, no ‘instant’.

So if our view of space and time is at best a convenient fiction, and at worst completely erroneous, what are the alternatives?

Bergson’s duration

The first person who challenged the classical notion of Newtonian time in the public’s imagination was probably Albert Einstein, who needed to establish a different concept of time in order to explain general relativity.

Einstein showed that there was no universal time, and that the present moment and the passing of time were relative to the observer. In effect, there were many times depending on one’s position in space. ‘Time is relative to systems of reference (different observers), and therefore irreducibly plural’ (Roffe, 2020, p.93).

Henri Bergson came to international prominence by arguing that the young genius physicist was wrong in this regard. Although Bergson thought Einstein had done more than anyone to challenge the classical conception of time, he believed Einstein had really only replaced one spatialised concept of time with another.3

Bergson, by contrast, proposed a notion of time that was far more radical.

Time, Bergson argued, should not be thought of as the continuation of a series of discrete moments — like the 16 frames per second of an old motion picture — but rather as the continuation of change.

Bergson rejected the idea of a single, universal, homogenous, quantitatively measurable concept of time. He rejected the idea of time as an arrow, running from the past through the present and into the future. And he also rejected conventional notions of causality, which relied upon the idea that past events manifested in the present.

Bergson instead argued that there was only one ‘time’ and that it was constantly moving. The past was not a reference to something now gone, but an expression for a virtual state that was as real as the present.

Many possible presents were possible — giving us what we might understand as the ‘future’ — and so the present was not a mirror of the virtual, but merely an actualisation of one possible event among many. The past does not precede the present, but is endlessly folded, unfolded and refolded into it.

And to get away from the spatialised language of time, Bergson used the word duration and spoke of its contraction, relaxation and expansion of time rather than its location before, behind, or in front of us.

Duration for Bergson was multiple, unmeasurable, relational, enfolded, continuously flowing and changing, and its effect on philosophy in the C20 has been profound.

Whitehead’s process philosophy and his concepts of concrescence and actual occasions owe a huge debt to Bergson, as does Heidegger’s work on ‘ungrounding’. But it is probably in Deleuze’s work that Bergson’s duration finds its most important and compelling expression.

The Deleuzian difference

Deleuze more than anyone revived interest in Bergson. Having been internationally famous in the 1920s, Bergson fell out of favour particularly among analytic philosophers in Britain and North America, and he was little studied until the latter part of the C20.

But Deleuzian concepts like the plane of immanence, territorialisation and deterritorialisation, the time image and movement image, and his own construction of the past, present and future in his three syntheses would not have existed without Bergson.

Take Deleuze’s concept of difference, for instance.

Difference is a fundamental idea for Deleuze. But Deleuzian difference is a very particular thing combining the idea of immanence from Spinoza and the idea of duration from Bergson.

Spinoza argued that there was no hard distinction between the physical and mental world. Indeed, he argued that there were no two ontologically separate substances, different in character, anywhere in the cosmos. There was no hierarchy between a superior one and an inferior other: no binary states at all; no transcendence, only the immanence of one substance shared by all things.

This kind of monism created a problem though, because how could we know the difference between one thing or another (God and man, for instance) if everything was the same? And how could new things emerge when all substance was fundamentally the same?

Deleuze answered this problem by showing that it is the way substance expresses itself that makes the difference. Expression here isn’t the product of some deeper-lying substance, but that which produces the attributes that give events, occasions and processes their character.

Expression is temporal, then. But, as I’ve argued, all existing models of time were fundamentally ‘spatial’. So Deleuze turned to the writings of Henri Bergson to explain the temporal quality of expression.

Rather than the production of new static structures from more fundamental matter, Deleuze proposed, following Bergson, that reality was a process of durational folding, unfolding and refolding, arguing that this folding conferred weight, meaning, pressure, and significance on events.

Deleuze finds examples of Bergsonian duration in lots of places: in Lewis Carroll’s writing, in Antonin Artaud’s howls and Francis Bacon’s paintings, in masochism and the schizoid personality, in the ‘streaming, spiralling, zigzagging, snaking, feverish line of variation’ (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987, p.499) found in sorcery and nomadism, in the cinema, and in the ‘baroque movement of endless foldings and unfolding’ of Leibniz (Deleuze, 1993, p.139), and Nietzsche’s eternal return.

So where space is a ‘multiplicity of exteriority, of simultaneity, of juxtaposition, of order, of quantitative differentiation, of difference in degree; it is numerical multiplicity, discontinuous and actual’, duration is ‘an internal multiplicity of succession, of fusion, of organisation, of heterogeneity, of qualitative discrimination, or of difference in kind; it is a virtual and continuous multiplicity that cannot be reduced to numbers’ (Deleuze, 1988, p.38).

What does this mean in practice?

Perhaps without realising it, people may be have been looking for alternative ways of thinking durationally for some time now.

Most health professionals recognise the limitations of quantitative measurement and its reductive focus on time. Quantitative chronological time just can’t account for the the fluidity, ambiguity and plasticity of time that we see all the time in real clinical practice. But phenomenological time also has its problems: its resistance to measurement, its humanism and, from a process perspective, its pursuit of static ‘being’, being not the least of these.

Some have looked to putatively ‘holistic’ models of health like the biopsychosocial model as a way to break with the Western view of time, but these have only shown so far a very limited ability to depart from the fundamental tenets of rational Western scientific thought.

Some have turned to indigenous cosmologies and ancient forms of wisdom like Buddhism and Hinduism for alternative approaches to time, but many indigenous cosmologies are fundamentally transcendent (relying deeply on spiritual domains ‘beyond’ this world), and many ancient wisdom traditions work better as modes of living than as explanations for the fundamental nature of reality.

Of course, we should remember that the primary reasons for holding on to a classical notion of clock time are tied to the West’s pursuit of unlimited growth and capitalistic efficiency, the management of time and labour, and the Protestant tradition tying work to salvation and human flourishing. (Think here of the importance for commerce of standardising Greenwich Mean Time.) So the arguments for a different way of thinking about time as duration will not take root simply because they are more ontologically accurate.

Perhaps this is why an enormous amount of attention has been directed towards quantum physics in recent years.

Quantum physics and quantum mechanics attempt to overturn centuries of Newtonian mechanistic thinking in science.

Tellingly, they have a huge amount of resonance with Bergsonian and Deleuzian philosophies of flux and flow, movement and duration. Physics and philosophy singing the same tune, you might say.

Quantum physics argues that time and space are constructed in the present and are not pre-existing states to which the present ‘refers’. Quantum physics provides empirical evidence for concepts like superposition (as a way to explain consciousness, for instance), wave-particle duality, uncertainty, entanglement, and the existence of many simultaneous instances of time4 — all concepts that defy conventional scientific wisdom and conform much more closely to process philosophies.5

Perhaps, then, we need to start thinking about health and illness in durational terms?

How would concepts like pain, disease, depression, healing, and therapy change if we looked at them as temporal/durational events rather than spatially-bound ‘things’?

How might our assessments, tests and treatments alter if our goal was durational flow rather than definitional clarity and stasis?

How might we reimagine cause and effect when the past isn’t something lying behind us in psychological memory but is folded into the present?

In the next post I’ll try to tackle a question at the heart of new thinking about duration, and one of real significance in healthcare, and that is the subject of movement, and how this too might also now by up for revision.

Part 5 - A kinetic theory of everything

Thus far in this series on process philosophy I’ve argued that nothing in the world is ever static, that there is no transcendental realm ‘beyond’ this world, and that there is no singular, standard, universal time regulating life.

From all of this you might imagine that these interlinked arguments were all features of a thoroughly worked-through philosophy of process, movement, flux and flow. But that’s not the case.

Until very recently, there has been no definitive way to think about process in Western philosophy.

Certainly there have been enormous theoretical advances, but until Thomas Nail’s 2024 book The Philosophy of Movement there has been no distillation of all of this scholarship into a coherent philosophical system.6

The Philosophy of Movement is the distillation of a decade of scholarship (12 books in 12 years) that began with Nail’s study of migration and borders, but now encompasses a vast field ranging from the works of Lucretius and Aristotle, Bergson, Kant, Marx, Whitehead, Deleuze and Guattari; space-time and quantum mechanics; cultural studies, history, art and architecture; OOO and the new materialisms; theories of objects, earth, and image; the writings of Virginia Woolf; psychology and noise studies.

At the outsetThe Philosophy of Movement tries to answer a simple question;

‘Why have some of the greatest minds of Western history dedicated their lives to the discovery of something genuinely immobile that could explain why things move? The Greek philosopher Aristotle imagined an “unmoved mover” who first propelled and gave order to the cosmos. The ancient scientist Archimedes imagined that if he had a fixed fulcrum and a lever long enough, he could move the earth. Later, the seventeenth-century French philosopher René Descartes reinterpreted Archimedes’s fulcrum as a point of “certain knowledge” from which the rest of moving reality could be objectively known. Most modern thinkers, such as Descartes and Isaac Newton, also shared a belief that God was like an unmoving clockmaker who set our mechanical universe in motion while he remained still. Even Albert Einstein’s incorrect theory that we live in an finite “block universe” was part of the centuries-long effort to explain motion of something immobile’ (Nail 2024 p.2).

Nail argues that our entire system of thought makes sense of movement only by reference to a static world that itself doesn’t move.

We seem determined to explain movement away.

Which is odd, really, given that we don’t try to explain such grand concepts as time and space away. Instead we try to give compelling accounts of them and and validate their existence.

So why have we worked so hard to invalidate movement’s existence and its fundamental role in explaining how the world works?

Nail argues that this prejudice against movement goes back to our earliest systems of thought.

The early Greek philosophers believed that the universe was a giant spinning sphere with an absolute immobile core. Aristotle conceived of an ‘unmoved mover’ to explain purpose in the universe. World religions argued for the role of eternal god(s). Descartes looked for unquestionable, unchangeable first principles to explain events. Modern science looked for deterministic, immovable, constant, and universal laws of nature. Linguists created vast taxonomies of fixed things. Political theorists tried to establish first principles and moral absolutes. Evan the Kantian phenomenologists attempted to explain everything in the phenomenal world in terms of stable essence and concepts like being and identity.

For much of human history, then, movement has been seen as a ‘derivative and passive’ accidental side-effect of stasis (Nail 2024, p.3).

And this has had enormous consequences that extend far beyond esoteric questions of ontology and epistemology.

It allowed Western Man, for instance, to invent a Great Chain of Being that saw ‘stable’ and immobile things like the mind, reason, detachment, objectivity, form, the laws of nature, and God as superior to anything that was inherently mobile.

Things that were mobile: nature, bodies — women’s bodies especially — the weather, animals, viruses, were seen as inferior, lacking limits and reason, aimless, having no constituency or political voice, de-formed, unsettled, they are matter out of place, unbounded and indeterminate. They can be neither grasped nor defined.

People who lived in settled homes and communities, in orderly cities with strong established political systems and long-establishes social hierarchies were considered the Enlightened ones. While immigrants, nomads, vagrants, free thinkers, anarchists, the neurodivergent and non-conformist, crip and queer were labelled as mad, bad, dangerous, unruly, primitive and corrupt.7

The Philosophy of Movement rejects the whole premise that movement is a by-product of stasis, arguing instead for movement as first philosophy.8

What this means is that there is nothing before or outside movement.

The key principles underpinning Nail’s philosophy are that movement is:

Indeterminate, meaning that movement follows no pre-defined line, path, or fixed background, but is in a constant process of metamorphosis (Nail 2024, p42)9

Relational. This is not the kind of relation that links one determinate thing to another: there is no ‘A meets B’ here (see #1 above). Rather, relation is a metastable process that affects all change, everywhere, all the time and all at once. Or as Nail puts it, it is a ‘degree of simultaneous reciprocal change in an open process’ (p.44)

Processual. Again, this is not a process happening to a ‘thing’, as we often conceptualise it. Rather it is change in the nature of change itself

So, as Nail sees it, metastable states — what others call matter, objects and things — result from movement, not the other way around;

‘Energy flows in, cycles through, and then flows out — of everything. Structure and form are the metastable by-products of energetic flows. We should think of forms not as fixed, unchanging entities but as fabrics woven from crosscrossing threads’ (p. 50).

Nail argues that a philosophy of movement should not only be theoretically robust, but that it should be real. A philosophy of movement should be palpable and verifiable.

To that end, Nail offers literally hundreds of examples drawn from the natural world, geology, art, politics, aesthetics, science, religion, epistemology, and many other fields, of the way energy is in a constant process of dissipation and entropy, spreading out in fractal, dendritic patters from ‘hot’ to ‘cold’ states.

Nail sees four broad patterns of movement repeating throughout the universe:

Centripetal motion - where flows are gathered and organised into denser areas (think here of cities and towns, organised religions, the formation of planets, metastable states like mountain ranges, animals and plants)

Centrifugal motion - flows moving from organised, low entropy states to dissipated high entropy energy states (i.e. dendrites, river deltas, birth, the big bang, viral spread)

Tensional motion - the dendritic spreading out of energy with each of the distinct branches being held together and pushed apart at the same time (families, trees, stars and galaxy clusters, orbital motion, books, knowledge)

Elastic motion - adaptive and responsive expansion and contraction to prevent adapt to environmental conditions (colonialism, capitalism, leaves, music, dark matter)

Perhaps more than any coherent philosophical system developed so far, Nail’s philosophy of movement conforms to all of the principles of process philosophy:

It describes immanence without any recourse to a transcendental realm ‘beyond’ this world

It is about a constant generative process of creation and does not repeat a spatialised notion of linear time

It assumes no fixed identities, beings, or matter

And, perhaps most importantly, it is universal

Although Nail’s philosophy of movement has been a decade in its maturation, it is early days for its critical reception. Time will tell whether others see it as the distillation of pure process philosophy, and how it might be applicable for future research, thought and practice.10

So, with that, it seems like this is the right place to wrap up the theoretical parts of this series.

In a couple of week’s time I’ll try to pull all of this together, draw out some more explicit links to healthcare, and recommend some readings and resources if you’re interested in thinking more about process philosophy.

Until then.

Part 6 - Some practical applications, resources and readings

Over the course of the last six episodes I have attempted to sketch a broad picture of process philosophy, an approach that is garnering advocates and critics in equal measure.

Process philosophy seems to appeal most to people who are frustrated with traditional ways of thinking, be it bio-scientific, subjectivist or critical, and centres around their unexamined humanism, transcendentalism, and static substance-based metaphysics.

But if you were interested in doing more process philosophy yourself, where could you start? First some practical suggestions, then some resources and reading recommendations.

Practical implications

To be schooled as a Western researcher or trained in a Western health profession is to be inculcated into a world of stable, quantifiable, taxonomically identifiable ‘things’ that function as an incredibly effective but no less abstract and disconnecting screen for the constantly churning, folding, contracting and relaxing, thickening and loosening processes that really makes up universal life.

So the first thing to say about practical implications of process philosophy is that to do it properly is very hard. There is simply too much invested in substance-based thinking in our schools, universities, workplaces, media and social systems to allow for much fluid thought.

There are openings, though, for all of us, through creative side-projects, speculative works in theory, and playful experiments in doing something different that can, if only briefly, explore a world beyond the mundane demands of paying the ferryman.

That might involve finding new modes of expression, like Oulipo-style experiments in writing, avoiding all forms of measurement (so no clocks, tape measures, questionnaires, scores and scales), or purposefully rejecting the conventions of mainstream quantitative and qualitative research.

It might mean deliberately avoiding any reference to bodies or minds in an ‘organised’ sense (think here of Deleuze’s bodies-without-organs), or being aware of our tendency to animate and ‘enliven’ brute matter with references to relational acts, assemblages or induced forms of motion, thereby ignoring our inadvertent assumption that matter was stable to begin with.

(Human) language itself might be a problem (think here of Deleuze’s ‘schizo’). So new modes of expression through sound, image, mathematics, or performance might be generative.

Breaking with the idea that inquiry should be purposeful, goal-directed, teleological, or guided by transcendental rules, social conventions, or norms might also be a fruitful way to break free from the world of productivist research thinking and practice with which we are all so familiar.

And what about writing something — or even just thinking something! — that doesn’t rush to be understandable, effective, powerful or translational?11 Instead, follow Deleuze’s primary motivation and try to produce something radically new.

‘Deleuze never provides an interpretation of the thinkers he is discussing; he is uninterested in hermeneutics, uninterested in teasing out ambiguities and contradictions, uninterested in deconstructing prior thinkers or in determining ways in which they might be entrenched in metaphysics. All this is in accord with Deleuze’s own philosophy: his focus is on invention, on the New, on the “creation of concepts.” It’s not a matter of saying, for instance, that Plato and Aristotle and St. Augustine were wrong about the nature of time, and Kant or Bergson are right. Rather, what matters to Deleuze is the sheer fact of conceptual invention: the fact that Kant, and then Bergson, invent entirely new ways of conceiving time and temporality, leading to new ways of distributing, classifying, and understanding phenomena, new perspectives on Life and Being. A creation of new concepts means that we see the world in a new way, one that wasn’t available to us before. This is what Deleuze looks for in the history of philosophy, and this is why (and how) he is concerned, not with what a given text “really” means, but rather with what can be done with it, how it can be used, what other problems and other texts it can be brought into conjunction with. Deleuze writes about philosophers whose ideas he can use, or transform, in order to work through the problems he is interested in’ Link

The writings of people like Deleuze and Whitehead especially are famously obtuse (although Bergson and Nail are much more accessible). But what many readers don’t understand is that they are not trying to be your friend. Deleuze especially is trying to break with the pedagogical convention of centuries of philosophy by not leading you, the reader, down an arrow-straight floral path from one logical proposition to another until you arrive at the conclusion the writer intended all along. If anything, he’s trying to get you lost, destabilise you, throw you into the weeds, and make you find your way out. So perhaps his example is in part designed to give you some encouragement to try the same thing for yourself; even if it’s only for a moment?12

This is all very daunting but reading more process philosophy can certainly help.

So, if you are keen to go deeper and explore ways you might think as flow not fixity, here are some tentative recommendations.

Key readings

Thinking with Whitehead - Isabelle Stengers’ comprehensive introduction to Alfred North Whitehead’s work. Stengers has used Whitehead’s work extensively and is also a deep reader of Deleuze, so makes lots of connections between the two. You could try to read Whitehead’s seminal Process and Reality but it is considered one of the most obtuse books in the philosophy, so perhaps start with some secondary literature, such as Matthew David Segall’s excellent Footnotes2Plato Substack site.

For a Pragmatics of the Useless - Erin Manning’s 2020 book gives a practical guide to thinking with Whitehead, Deleuze, Massumi and others, and using these authors to offer new insights into neurotypicality, black studies, autism, and language.

Living in Time - Barry Allen’s very readable introduction to the work of Henri Bergson — a readable philosopher in his own right. Covering all of Bergson’s major works and themes, including consciousness, creative evolution, duration, intuition and memory, Allen explains why Bergson’s work proved so shocking in the early C20, but also why people are now turning back to his ideas, especially in areas like quantum physics and consciousness studies.

Difference and Repetition - Along with Logic of Sense, perhaps the greatest of Deleuze’s masterpieces. D&R is perhaps the best distillation of Deleuze’s development of process philosophy. These books came after his critical readings on Bergson, Hume, Kant, Leibniz, Nietzsche, and Spinoza but before his anti-oedipal collaborations with Félix Guattari. Along with What is Philosophy? D&R and LoS marks the clearest statement of Deleuze’s metaphysics.

The Philosophy of Movement - Thomas Nail’s most recent work and the summation of a decade of books beginning with migration studies and ending with a thoroughgoing and highly original critique of the stasis underpinning everything we think in Western science. Highly recommended.

References and some additional readings

Angulo, D., Thompson, K., Nixon, V., Jiao, A., Wiseman, H. M., & Steinberg, A. M. (2024, September 5). Experimental evidence that a photon can spend a negative amount of time in an atom cloud. arXiv.org. Link

Asuquo, G. O., Umotong, I. D., & Dennis, O. (2022). A critical exposition of Bergson’s process philosophy. International Journal of Humanities and Innovation, 5(3), 104–109. Link

Bergson, H. (1910). Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness (F. L. Pogson, Trans.). F.L. Pogson. Swan Sonnenschein.

Carlyle D. (2019). Walking in rhythm with Deleuze and a dog inside the classroom: being and becoming well and happy together. Medical humanities. Link

De Boer, T. J. (2022). The Philosophy of Henri Bergson. Bergsoniana, 2. Link

Delafield-Butt, J. (2012) Whitehead's philosophy of organism, satisfaction, and mental health. In: Mental Health and the Disciplines Symposium, Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, The University of Edinburgh.

Deleuze, G. (1988). Bergsonism. Zone Books.

Deleuze, G. (1993). Difference and repetition. Columbia University Press.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus — Capitalism and schizophrenia (B. Massumi, Trans.). University of Minnesota Press.

Godfrey-Smith, P. (2024). Living on Earth: Forests, Corals, Consciousness, and the Making of the World. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Goff, P. 2023). Why? The Purpose of the Universe. Oxford University Press.

Goldhill, S. (2024). Beyond Michel Foucault, Beyond Peter Brown: What Did Early Christianity Destroy?Arethusa 57(2), 193-225. Link

Hallword, P. (2006). Out of this world: Deleuze and the philosophy of creation. Verso.

Hossenfelder, S. (2022). Existential Physics: A Scientist’s Guide to Life’s Biggest Questions. Atlantic Books.

Hughes, J. (1997). Lines of flight. Sheffield Academic Press.

Hunt, T. (2024, March 26). What is “process philosophy” and who is Alfred North Whitehead? Medium. Link

Kemper, J. (2024). Deep Time and Microtime: Anthropocene Temporalities and Silicon Valley’s Longtermist Scope. Theory, Culture & Society, 41(6), 21–36. Link

Lakoff, G. and M. Johnson (1980). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press.

Lapoujade, D. (2017). Aberrant Movements: The Philosophy of Gilles Deleuze. MIT Press.

Lenton, T. M., Dutreuil, S., & Latour, B. (2024). Gaia as Seen from Within. Theory, Culture & Society. Link

Lettow, S., & Nessel, S. (2022). Ecologies of Gender: Contemporary Nature Relations and the Nonhuman Turn. Routledge.

Massumi, B. (2014). What Animals Teach Us about Politics. Duke University Press.

May-Hobbs, M. (2023, October 23). Henri Bergson’s Philosophy: What is the Importance of Memory? TheCollector. Link

Mermin, N. David. “What’s Bad about This Habit”, Physics Today 62 (2009), pp.8-9. Link

Montag, W. & Stolze, T. (eds) (2008). The New Spinoza. University of Minnesota Press.

Nail, T. (2024). The Philosophy of Movement: An Introduction. University of Minnesota Press.

Nail, T. (2023). Matter and Motion: A Brief History of Kinetic Materialism. Edinburgh University Press.

Nail, T. (2021). Theory of the Earth. Stanford University Press.

Nail, T. (2021). Theory of the Object. Edinburgh University Press.

Nail, T. (2020). Marx in Motion: A New Materialist Marxism. Oxford University Press, USA.

Neven, H., Zalcman, A., Read, P., Kosik, K. S., van der Molen, T., Bouwmeester, D., Bodnia, E., Turin, L., & Koch, C. (2024). Testing the Conjecture That Quantum Processes Create Conscious Experience. Entropy (Basel), 26(6), 460. Link

Nielsen, T. H. (2024). The Dynamics of Disease: Toward a Processual Theory of Health. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy: A Forum for Bioethics and Philosophy of Medicine, 49(3), 271–282. Link

Orf, D. (2024, August 13). Quantum entanglement in your brain is what generates consciousness, Radical study suggests. Popular Mechanics. Link

Padavic-Callaghan, K. (2024, September 5). Can we solve quantum theory’s biggest problem by redefining reality? New Scientist. Link

Robert Mesle. C. (2008). Process-Relational Philosophy. Templeton Press.

Roffe, J. (2020). The works of Gilles Deleuze: Volume 1 - 1953-1969. re.press. Link

Rovelli, Carlo (2020). Helgoland. Penguin.

Schönher, M. (2019). Gilles Deleuze’s Philosophy of Nature: System and Method in What is Philosophy. Theory, Culture & Society. Link

Shaviro, S. (2014). The Universe of Things: On Speculative Realism. Posthumanities.

Sölch D. Wheeler and Whitehead: Process Biology and Process Philosophy in the Early Twentieth Century. J Hist Ideas. 2016 Jul;77(3):489-507. Link

Wagh, M. (2024, September 26). Your consciousness can connect with the whole universe, groundbreaking new research suggests. Popular Mechanics. Link

Wood, C. (2024, September 25). The Thought Experiments That Fray the Fabric of Space-Time | Quanta Magazine. Quanta Magazine. Link

Whitehead, A. N. (1929/1978). Process and reality. Free Press.

Deleuze and Guattari’s distinction between the virtual real and the actual seems to offer a form of transcendence, as does Alfred North Whitehead’s central concept of God and beauty. Graham Harman’s reference to real objects/qualities and sensual objects/qualities also suggests an unreachable realm beyond the world of experience.

Tennessee Williams once described time as ‘the longest distance between two places’.

There are even studies in quantum physics showing evidence that time can flow backwards.

For more on the possibilities of quantum physics, see, Rovelli, 2021; Angulo et al, 2024; Hossenfelder, 2022; Kemper, 2024; Neven et al, 2024; Orf, 2024; Padavic-Callaghan, 2024; Wagh, 2024; Wood, 2024.

Some might argue that Bergson, Whitehead and Deleuze all provided coherent processual systems, but each one has been criticised in various ways for being vitalist, materialist, and transcendental in different ways.

Enlightenment in many languages refers to whiteness, whereas blackness and darkness are often relegated to the bottom of the hierarchy.

Although Nail’s work recognises a strong debt to the work of Henri Bergson, Alfred North Whitehead, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, the vitalists, new materialists, actor network theorists and speculative realists of the last century, he is at pains to show the important ways his approach differs from all of theirs.

Nail draws heavily here on the Lucretian concept of the ‘swerve’ to explain how and why movement moves this way.

Nail’s latest book project is provisionally titled Pink Noise and looks at 1/f patterns of motion are quite important to nearly everything including physical and mental health. Here is a short excerpt from the end of Chapter 1, still in draft form (so please don’t cite yet); ‘For the first time in history, a whole new wave of experimental and clinical researchers is building on spontaneous brain noise to understand consciousness, treat mental illness, and uncover the creative power of our non-conscious mind. The science of flux is far from solving all the mysteries of the brain, but we now know enough to see that a Copernican revolution has arrived that is already starting to change everything scientists and philosophers thought they knew. Its consequences go far beyond the realm of neuroscience. Flux is pushing us to reimagine evolution, society, how our thoughts evolved from non-conscious matter, how we design artificial intelligence systems, and how we care for ourselves and one another. With any luck, the future will be pink.’ The book will be out in 2025.

There are some astonishing works of literature that do this. Think James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake, Karl Ove Knausgård’s My Struggle, Samuel Beckett’s How It Is, and Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity's Rainbow. Note also that most of the major works of process philosophy listed below have been criticised for being dense, layered with complex language, difficult to read and understand.

It’s probably also worthwhile remembering that continental philosophers are not the only ones who like obtuse language and jargon. Just think about what you had to learn to become a health professional! All those latin words for body parts, complicated physiological processes and technical terms. Process philosophy language is only hard because it’s unfamiliar. Reading more of it — like studying the Krebb’s cycle or revising the origins and insertions of adductor longus — can really help.

This is heavy material. I am definitely curious about process philosophy, so I will follow your advice to read. Thank you for challenging taken-for-granted understandings and insights.

Great to have these posts together like this. I have some questions about the ethical (existential) “I” in relation to process philosophy. Is it possible to conceptualise my own freedom to choose how to act in a process-based paradigm?